University Tackles Students’ Most Basic Needs: Housing and Hunger

Several orange flags are staked on Glenn Lawn symbolizing estimated 7000 students that suffer from food insecurity on Monday, February 13, 2017 in Chico, Calif. As part of Philanthropy Awareness Day, the Student Philanthropy Council (SPC) were raising awareness to the donors and impact of giving in regards to student food insecurities. (Jason Halley/University Photographer)

Andres Martinez felt like a fraud.

To outsiders, the physical geography major was making the most of college life, attending any and all club meetings, information sessions, and receptions. But it wasn’t really interest in the subject matter that drew him to each event—it was the promise of free food.

Desperate to eat and with no money for groceries, Martinez was forced to set his morals aside to ease his hunger pangs.

As an undocumented student, Martinez could not legally work when he started college, and financial aid barely covered the cost of his tuition and rent. At times his struggle felt insurmountable. He hated even more that his grades were slipping because he didn’t have the nutrition he needed to focus.

“It feels like a border that just grows as you try to cross it,” he said. “It somehow made me feel less than everyone, as if I wasn’t equal because I couldn’t give it my all. I remember being so scared of what could happen next.”

Martinez’s story has become a common narrative across college campuses, where rising costs and changing student demographics have made food and housing insecurity a growing trend. The consequences can be devastating—undermining educational success and derailing the promising futures of hundreds of thousands of students.

A 2016 report showed that nearly one in four students in the California State University system are going hungry. Further research suggests that 46 percent of Chico State students struggle to afford food and one in every 12 students lives in unstable housing situations.

“The perfect storm is happening,” said Joe Picard, project director of the new Chico State Basic Needs Project. “If we are going to graduate folks, they need their basic needs supported.”

The Shifting Student Demographic

The cost of attending a public university has risen dramatically in the last two decades. At Chico State, the cost of tuition, fees, and books has more than doubled since 2004 to $9,200 a year. Combined with room, board, and other living expenses, costs total around $24,000.

In comparison, full-time employment on minimum wage in California nets a gross annual salary of $21,840, or a mere $1,820 a month.

Like many, Picard was unaware until recently that so many students were struggling.

“What woke me up was looking at the economic challenges facing our changing demographic,” he said, noting Chico State has seen a marked shift in his 20 years on campus.

More than 30 percent of students now identify as Hispanic or Latino, more than 50 percent are the first generation in their family to graduate with a four-year degree, and 50 percent are eligible for Pell Grants.

The US Department of Education reports that nationally, roughly 74 percent of today’s college students are nontraditional and find it difficult to support themselves and pay for college. They often lack a critical support network during their path to future social mobility.

Getting a Handle on Hunger

Kathleen Moroney, an administrative analyst for the Vice President for Student Affairs Office, said her awareness into the depth of food insecurity started several years ago when a professor called to see if the campus had a food pantry. She was shocked to learn the answer was no. Instead, she learned students were referred to a local homeless shelter and food bank, and many staff members on the frontlines of student interaction kept food in their drawers because hunger was so prevalent.

She immediately set forth in a crusade for a solution, finding an empty office with two bookcases and filling them with canned and dry goods like soup, beans, pasta, and tuna. Pantry users came by referrals and word of mouth—as they still do today.

Since 2013, the Hungry Wildcat Food Pantry has provided 28 tons of food assistance to more than 2,750 students, representing more than 46,000 meals. The pantry also provides hygiene products and referrals to campus and community services for students in need.

“The first student was pretty uncomfortable,” Moroney remembered. “She didn’t want to give her name. She felt awkward asking for help.”

Moroney walked with subsequent students from her office to the Student Services Center’s makeshift pantry, listening to their stories of choosing between food and rent, food and tuition, food and utilities.

Moroney, now credited as the founder of the Hungry Wildcat Food Pantry, knew Chico State had to provide them some relief. And when she saw students’ reaction to the pantry, she knew she was doing the right thing.

“Just seeing the food available, you could see it in their eyes,” she said. “They were so grateful, humble, thankful that we were doing this. I would say, ‘We want you to be successful.’”

And yet, no matter how desperate they were for food, so often she saw their hesitancy—not wanting to take too much, always thinking someone else might need it more.

Martinez knows well the surprise in students’ eyes when they come to the pantry for the first time.

He explains to quiet and unsure students that food is a right and a resource, just like the Counseling and Wellness Center on campus. They can’t expect to advance until they take care of themselves at the most basic levels.

“You don’t have to use it but if you want to—if you need to—it’s there,” he said. “It’s help, because we all need help.”

The geography major relied on the pantry a lot his freshman year. His sophomore year, his Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals status came through, enabling him to get a job on campus. Today, he is an intern and a tutor for the geography department, taking 18 units a semester, working 12 hours a week, tutoring for three hours, and spending three hours working at the pantry.

“I see myself in these students—‘This is food I can get? It’s just for me to take?’” he said, noting the joy they express when fresh items come in, like melons in summer or pomegranates in fall. “The simplicity of the pantry comes down to its honesty. It really truly helps, and it’s the most immediate help I see.”

Help with Housing

As Alejandra Balle looked at her bank account, the plant biology major wasn’t sure she would be able to return for her junior year. She considered moving back in with her foster parents, saving the rent money, and taking a break until she could afford college again.

“Everyone told me, ‘What are you doing? You have to pull through. Life doesn’t give you breaks,’” she said.

So Balle scraped together just enough to rent a room and returned to Chico, staying with a friend while her credit check processed. But when the friend’s roommate made uncomfortable advances toward Balle while she slept, she decided it was safer in her car.

Tucked in her backseat, hidden by tinted windows, no one could see her in the apartment parking lot. She would lie there, listening to people unlocking their cars and laughing as they walked through the lot on the way to bars or friends’ houses.

“Sleeping in the car felt like my own space. I wasn’t bothering anybody and nobody was bothering me,” she said.

Growing up, her family was “the poorest of the poor,” she said. Her mom is an undocumented immigrant from El Salvador, who fled to the United States because of war in her home country. She and her husband struggled to raise Balle and her seven siblings, and when they lost custody when she was 17, it was a blessing in disguise, Balle said.

She moved in with a foster family, making her eligible for financial aid and a state Chafee Grant exclusively for foster youth that pay her tuition and living expenses. Other grants for foster youth give her a living allowance.

Still, it’s not enough. Even in a moderately priced community like Chico, and despite her close relationship with staff mentors on campus, she couldn’t bring herself to reach out.

“I didn’t want to bother anyone,” she said. “Everyone thinks I have a pretty face and a good attitude and nobody thinks I came from a broken household. Nobody thinks I have a [messed-up] life.”

One day, working in the Student Affairs office, her story tumbled out to Moroney, who immediately connected her with emergency housing—one of the newest resources offered by the Basic Needs Project.

Rental prices in Chico have jumped by 30 to 50 percent in the last five years, with a room in a four-bedroom apartment costing between $350 and $650 a month. With vacant apartments in short supply, safe, stable, and affordable housing can be out of reach for some students, Picard said.

Nearly 10 percent of CSU students report living in unstable housing situations.

“It’s real. Students do live on couches and couch surf and trade sex for housing all the time,” Picard said, noting others, like Balle, live in their cars and a few utilize area homeless shelters when left with no other options.

The School of Social Work and offices of Financial Aid, University Housing, and Student Affairs have teamed up to provide short-term emergency housing for students in financial crisis and assist in long-term solutions. Off-campus housing director Dan Herbert said the fixes are as diverse as the students who need them but range from housing in residence halls and hotel vouchers to funding deposits and serving as a cosigner through the University’s relationship with housing providers.

Emergency housing was a bridge for Balle, helping her for just a few weeks until she moved into her apartment. Today, the first-generation student is planning a career in ethnobotany and dreams of getting her master’s or maybe even a PhD.

“I’m doing it for myself,” she said. “I want to set an example. I want to set the bar high. To set expectations that you can succeed and rise out of poverty.”

Path out of Poverty

For years, Moroney worked quietly and without support from administration, growing the small pantry she created in 2013 as she tried to keep up with student demand.

When new president Gayle E. Hutchinson arrived on campus, she stopped Moroney in the hallway one day and thanked her for shining a light on the need. It was a focal point in the president’s 2016 convocation address, and support continues to grow.

Initial pantry support came as a $20,100 allocation from the Associated Students Sustainability Fund. That funding has enabled the pantry to become the No. 1 customer of the University Farm’s Organic Vegetable Project, purchasing student-grown produce for the pantry and fostering a mutual education experience.

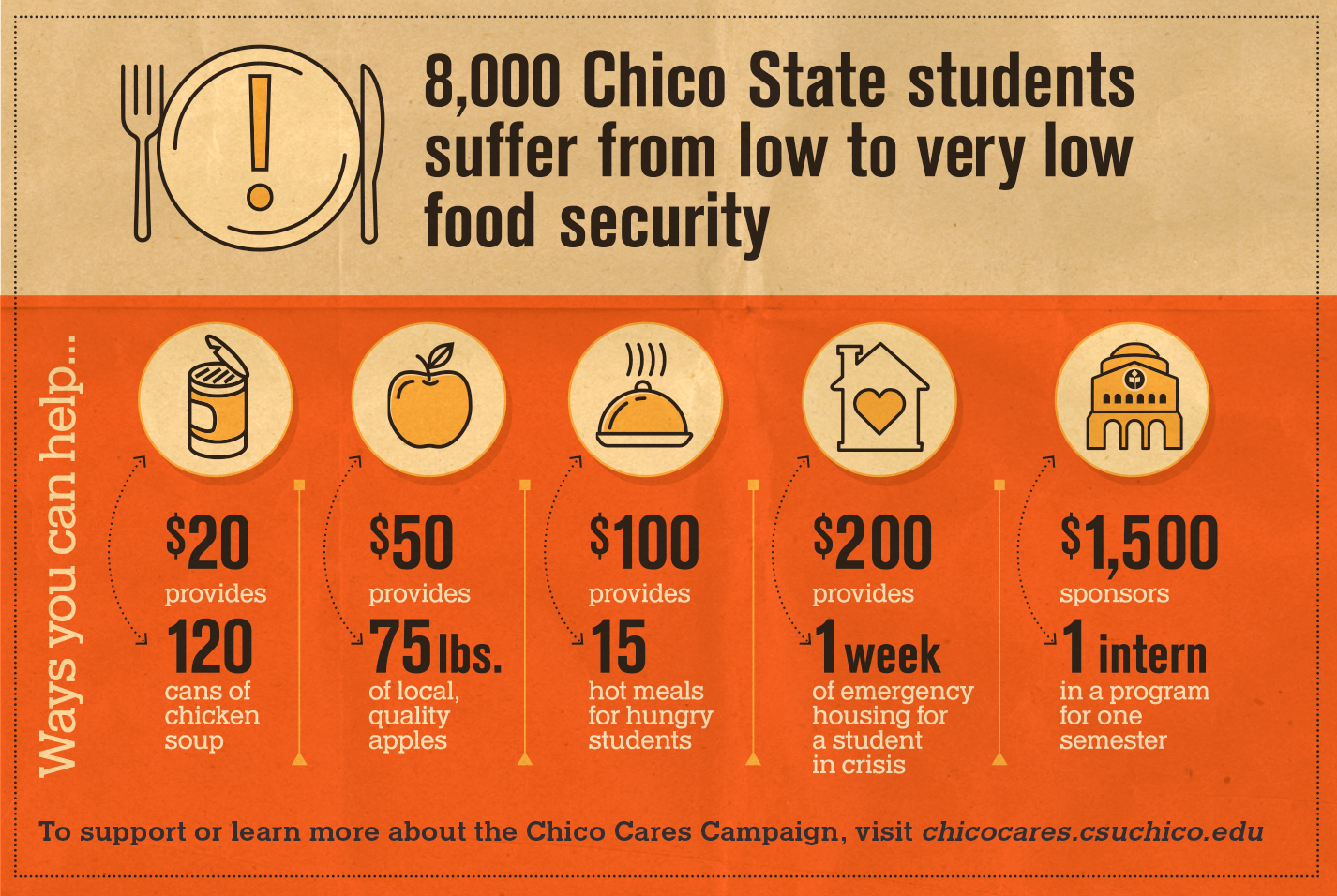

Additionally, the Student Philanthropy Council helped raise $13,000 as the 2017 senior class gift. The California Faculty Association’s Chico Chapter pledged $12,500 in matching funds to support an endowment for long-term support, and now the Chico Cares Campaign aims to raise $50,000 by Giving Day on November 28 to ensure the University can meet students’ needs this year.

The pantry has been astounded by the support of the community, with donations from the Soroptomists, the Chico Breakfast Lions Club, the Salvation Army, the Jesus Center, the Catholic Ladies Society, the Chico Food Project, the North State Food Bank, and other groups, which have donated everything from canned goods to a commercial refrigerator.

“We know this can of green beans isn’t going to change a generation, but there are so many students who are living on that bubble—it’s one thing that stops them from dropping out,” Moroney said. “Education truly is the best way out of poverty.”

Additional resources have included healthy meal access for students in immediate need and a mobile food rescue alert system to text students when University catering events have leftover food.

Through the support of CalFresh Outreach and Chico State’s Center for Healthy Communities (CHC), the Basic Needs Project helps students apply for CalFresh, which is California’s USDA SNAP supplemental food program. They enrolled 21 students in on the first day of the fall semester.

“We let the students know that CalFresh assistance is a benefit—like financial aid for food—so they can move toward more permanent food security,” Picard said. “They are getting an education, and they are going to give back.”

Despite new eligibility requirements that make CalFresh more accessible than ever, student sign-ups remain low due to lack of awareness and stigma.

“No one wants to admit that they are poor,” Picard said. “They want to fit in. Part of this project is to say, ‘You’re not alone.’”

Stamping Out Stigma

Brandi Simonaro knows that experience all too well.

She worked full-time throughout college, always reminding herself it would pay off in the end. She chose Chico State because it had a lower cost of living and she assumed other students would share her experience. Instead, she felt alone.

“I thought we would be in this collective struggle,” she said. “But then, I thought, ‘Is it just me?’ It really felt like I was the only one.”

Her first semester, she thought about dropping out. Paying tuition and other expenses was just too much.

“It seems like it’s the right answer to drop out,” she said. “And that’s awful, because pushing through is so worth it. But in that moment, when your situation is so scary, it seems like the right answer.”

When a student intern from CHC came into her classroom to talk about food insecurity, a lightbulb went off.

“It was like, ‘Oh my gosh, they are talking about me,’” she said.

She began interning with the Center, where all students are initiated to their jobs by going through the eligibility process for CalFresh, learning what it takes to apply and raising awareness of how common eligibility is. Not only was Simonaro eligible, but she secured the highest monthly total—$194—to buy food.

After living off $75 a month, eating mostly rice and beans, it was a windfall. She knew her limited diet was doing damage to her mind and body, but she had no other choice. Suddenly, could cook healthier meals and worry less.

“The amount of stress it took off me to not have to focus on how I was going to eat, it’s incredible,” she said. “When you have to worry about where your next meal is coming from, you are not going to do well in your class.”

She knows there’s an accepted perception that college students live on Top Ramen.

“But when you are doing that, you are not feeling good. You are not going to do well on tests,” she said. “We teach people about eating well and chronic disease, and I was eating candy before class because it kept me awake.”

Once she had access to adequate food resources, her grades and performance soared, and she was able to graduate in two years. She’s now pursuing her MBA and works full-time at CHC, where she visits other campuses to help them start CalFresh outreach programs from scratch.

“I know there are thousands of students out there like me, and it makes me so sad,” Simonaro said. “They are sucking it up and driving through and that’s awesome, but we can help them.”

Dreaming On

In her fall convocation address this year, President Hutchinson made a promise to the campus community.

“Together, we will ensure that no student is hungry or homeless at Chico State,” she said. “It is paramount that we create a University experience where no student should have to make a decision between sufficient food and safe and reliable housing, and their education.”

In her message to campus announcing the Chico Cares Campaign to faculty and staff earlier this year, Hutchinson quoted nationally renowned financial aid scholar Sara Goldrick-Rab: “A college education is a great tool for overcoming poverty, but students have to be able to escape the conditions of poverty long enough to finish their degrees or we’re wasting their time.”

When Martinez was a child, his family was constantly on the move, from one apartment to the next, as his mother struggled to pay bills. Working in a restaurant, she did all she could as a single parent to support him, but attending so many schools left him feeling like an outsider.

At Chico State, he’s finally found his place with roommates who didn’t judge him for having only a jar of peanut butter in the fridge. Pantry staff who offered him a job. Friends and mentors who regularly encourage him on his path to his degree.

“I feel so embedded, I feel an anchor here,” he said. “I want to own this place.”

As the first in his family to pursue higher education, Martinez said an education at a four-year college is something every young person dreams of. Now here, he is pursuing his next goal: graduate and land a high-paying job in geographical information systems so he can do better for his family and for other struggling students who will follow in his path.

“I’m trying to find my dream here,” Martinez said. “Chico has shown me what it means to volunteer and give back. I want to be one of those people who can come donate to the pantry once a week or send that check of $25 to help students like me. This is my American dream.”

This story first appeared in Chico Statements.