‘All They Will Call You’ Aims to Honor Anonymous Plane Crash Victims

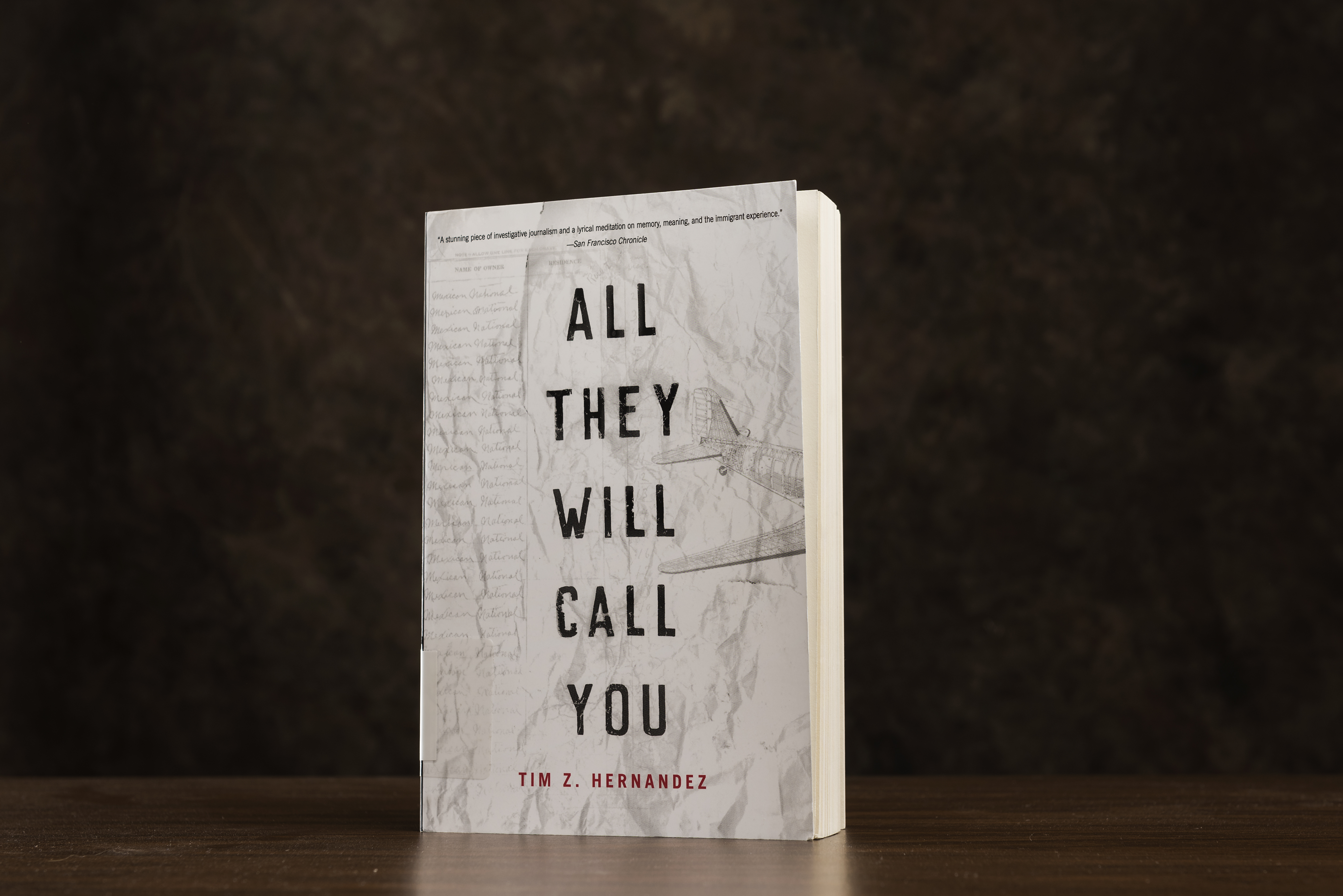

Last year, Chico State President Hayle Hutchinson and Butte College President Samia Yaqub jointly chose Tim Z. Hernandez’s “All They Will Call You” as the Book in Common for 2018-19.

(Jason Halley/University Photographer/CSU Chico)

A funny thing happened when author Tim Z. Hernandez was researching his fifth book. He found inspiration for his sixth book.

Conducting background research for his 2014 novel Mañana Means Heaven, set in 1947 in Fresno County, Hernandez uncovered an article about a January 1948 plane crash that claimed the lives of all 32 passengers—including 28 Mexican citizens—in California’s Central Valley.

While the horror of one of the deadliest plane crashes in California history was noteworthy enough, the story named the Douglas DC-3’s all-American flight crew but swept the Mexican passengers into the darkness of anonymity. This injustice spawned the song “Deportee (Plane Wreck at Los Gatos),” originally written by Woody Guthrie and performed by Martin Hoffman, and subsequently recorded by more than a dozen others, from Joan Baez and Willie Nelson to Johnny Cash and Ani DeFranco.

“At the time I’d been listening to Woody Guthrie’s music because I was using that as the soundtrack for [Mañana Means Heaven],” Hernandez said. “I was at the right intersection in that moment, and I realized this was the same incident Woody wrote that song about. What struck me was that mystery behind who these people are.”

His ensuing curiosity resulted in Hernandez’s sixth book, All They Will Call You, an exhaustive investigative piece detailing the lives of the Mexican nationals who died in the crash, as well as those of the flight crew.

Last year, Chico State and Butte College named All They Will Call You as the 2018–19 Book in Common, a shared community read designed to promote discussion and understanding of important issues facing the broader community. And on Wednesday, March 13, at 7:30 p.m., Hernandez, who has taught creative writing at the University of Texas at El Paso since 2014, will visit Laxson Auditorium to talk about his book.

In a conversation last week from his home in El Paso, Texas, Hernandez discussed the synchronicity of how his book came together, the emotion of interviewing family members of those who perished in the plane crash, and why the book is relevant more than 70 years later.

***

Chico State: How did you get started writing this book?

Hernandez: I found out they were buried in a mass unmarked grave within maybe two miles of my house in Fresno. I went and kind of just stood there by this anonymous mass grave in this anonymous plot. It was so moving to me that I just had to find the names of who they were. And that was genuinely the only bit of interest I even had … So I left it alone. I file it away and if it continues to bug me and nag at me for months, then I start to listen. And that’s what happened with this—that question kept burning in the back of my mind, “Who are these people?” … Throughout the process of writing this book, I lived in three different places. Fresno, where I’m from originally; Colorado, where I went to school and lived for 10 years; and El Paso. And each of these places had unique information that was vital to the book that was within an hour of my home. The musician, Martin Hoffman, who [originally recorded] that song, recorded it some 45 minutes from where I lived in Colorado.

I needed and wanted the find an exact replica of a Douglas DC-3 airplane, and I could never find one. Every time I was invited to a new city, I would always look for an airplane museum. No place had them. Then, I got a job in El Paso in 2014 and I move here, and a mile and a half from my house in El Paso there was this giant billboard that said, War Eagles Air Museum. A five-minute drive from my home and here it is, a fully renovated replica of the Douglas DC-3. They gave me access to sit inside that airplane, and that’s where I actually wrote scenes from the plane crash, sitting inside that plane. When I told the museum what I was doing, they really were excited about the project. They let me into the exhibit and I told them I’d been looking everywhere for this airplane and I’d love to see it. They said it’s fully restored inside and out. When I told them what I was doing, they said, “We will close off the exhibit whenever you want. Come in and sit in the airplane as long as you need and write inside of it.” Every time I wrote a scene from inside that airplane, I would sit in it. If I wrote a scene, for example, of what the pilot was seeing or doing in the cockpit, I wrote it right there in the cockpit.

What was your goal in writing the book?

Obviously, there are a lot of political aspects to the story, and one of the things I had to decide early on, and it was intentional, was that I was not writing about the political aspects of the situation. I didn’t want that story to get lost with all the other books that talk about the political rhetoric around immigration. I felt like this book had the opportunity to illuminate a different part of that conversation, which was about the human beings behind these policies and whenever we use abstractions, like the word “deportees” or “immigrants” or “aliens.” The first thing I wanted to do was to find and locate the families of every passenger on that airplane, not just the Mexican passengers. But it was critical that I also found the families of the pilots, the stewardesses and to highlight their lives, the things that they loved, the dreams they had, side by side with the same dreams, loves, and interests of the Mexican passengers. I wanted to elevate them all to the same level to show that we have more in common as human beings than we do differences. That’s the goal of the book, to show that we’re all in this ship together, hurtling toward one common fate.

(Jason Halley / University Photographer)

What was your writing process?

It was sort of a guerilla approach to my research. I don’t have a background in investigative journalism. My background is poetry. And at least in the first four years, from 2010 to 2014, I didn’t have access to any budget, it was all out of my own pocket. I had to make do with what I had. From my own home, I would find a family, say, in Bay City, Texas, that I suspected was related and the best way for me is always in person. I didn’t have any money to go out there, so I’d contact the nearest university or college in that area and tell them, “I’m an author, I’ll come out, and just for the price of an airline ticket I’ll do a reading for your students and sign books.” They’d fly me out, and while I was there, I’d take an extra day off, rent a car and drive over to where that house was and talk to these people. I was resigned to doing that kind of research. It wasn’t until I started to gain a little momentum that a lot of the research became more accessible and easier, I’d find archives and family members would start giving me more information and leading me to others that were connected to the story.

What was it like to talk to the families of the passengers?

It was a very emotional process, as you can imagine. For all of the families, it was a surprise. This is a story that they all knew and lived with growing up. Most of the families had never heard of the song, and never knew there was this song recorded by people like Joan Baez and Willie Nelson. In their family’s lore, they only knew they had a relative who once came to the United States and was killed in a plane crash. And they never knew what happened to that relative. They didn’t know where they were buried, where their remains were. Every time I sat down with a family member, they would immediately start to cry, especially family members who personally knew the passengers.

I talked to Carantina, 10-year-old daughter of Ramon at the time of the crash. She had vivid and fond memories of her father. The moment I sat down with her, she began crying. She said, “I’ve lived with this story for so long, I didn’t think that anybody cared, I didn’t know what happened.”

What obstacles did you confront?

One of the main obstacles was going into Mexico. I’m a fourth-generation Mexican American, a child of immigrants, a child of farm workers in the Central Valley. Four generations later, on all sides of my family, we’ve lost all contact to Mexico. I was not raised going to Mexico as a kid, I wasn’t raised close to that tradition or close to that reality. … The prospect of going to Mexico was frightening to me. I remember thinking, “I have to go to Mexico to do this work. Therefore, I’m going to have to get over it.” The good news is, I understand Spanish fluently, and I can speak it. If I’m speaking to folks who don’t have a lot of Spanish in their background, they wouldn’t know the difference. But if I’m in Mexico, it’s a different situation.

I ended up bringing along with me Guillermo Ramirez, who is actually related to two of the passengers. He actually ended up assembling a small research team for me, people who knew the area very well in these parts of Mexico, a driver, a woman who could document on video and audio for me. So I could just write and listen to these people. When we got to Mexico, Guillermo and I had had so many conversations about this that the first one of two interviews in Mexico, in my broken Spanish I would ask basic questions, like “Tell me the story of what you know about Ramon.” I couldn’t get more in-depth with my questions. What ended up happening slowly after the first few days, Guillermo would translate and go back and forth so often that he became the interviewer at times, whereas I was relegated to the role of witness. I realized I was witnessing one surviving family interviewing another surviving family and the conversation organically began to flow. Because I understood everything that was being said, I didn’t have to ask too many questions, I could just write and write and write.

Why is a book about immigrants in the 1940s relevant today?

We still hear that kind of rhetoric … not only from our politicians, but also from neighbors and family and friends. We still hear people being referred to as “deportees,” folks being referred to as “aliens” or “illegals.” People being referred to now as detainees, because of the kids being detained in the shelters. Labels like that are meant to do only one thing, to strip these people of their humanity. It’s easier for us to make these kinds of policies, to make these kinds of choices. And not even on the political level, but on the one-on-one level, it’s easy for a neighbor to hate another neighbor if we don’t know their name. The moment we know their name is the moment we have to reckon with their humanity, that they are a human being, that they have people they love and families. That’s what I hope is the one thing this book combats, the idea that we have a divisive line between us, whether the line is invisible or there’s a real wall. I want the book to convey that we have much more in common than we do differences, and the way we learn that is by sharing our stories.

What does the power of storytelling mean to you?

We all have stories. Every day our lives are made up of stories. We follow one narrative one way or another every single day. And we get to choose that narrative. If we are listening only to news threads or media slices, if we’re listening to others telling us who we are, then we tend to follow a negative narrative throughout our day, or a very daunting narrative throughout our day. If we remind ourselves who we are by sharing our stories with others, if we remind ourselves who the people in our community are by hearing their stories, that is a way to combat all of that paranoia and negativity around us. For me, the power of stories is the power of positivity. The more we share our stories, the better we feel about ourselves and, therefore, about our community. Stories are the nutrients of narrative.

What’s next?

This story is not done. I’d like to make a callout to the local communities, especially in that area in California. All of my research points to that these passengers’ families, the people who were part of this story, were between Fresno, Stockton, Sacramento, and Northern California, up to Chico. My hunch tells me that a lot of the research and the people who hold this history and people I still want to be in touch with, are in that area. I’m still researching. I’m actually working on a second installment of the story. Anyone who has any ties to this information, this story is living history right now. All people have to do is look up the list of names and ask their relatives if they know anything about it. I said that before, and I found another family member that way by making a callout. Chico and its community should know that this story is alive and I’m still looking and searching—and they could very well be a part of it, for all they know.