Campus Research Probes ‘Sit-Lie’

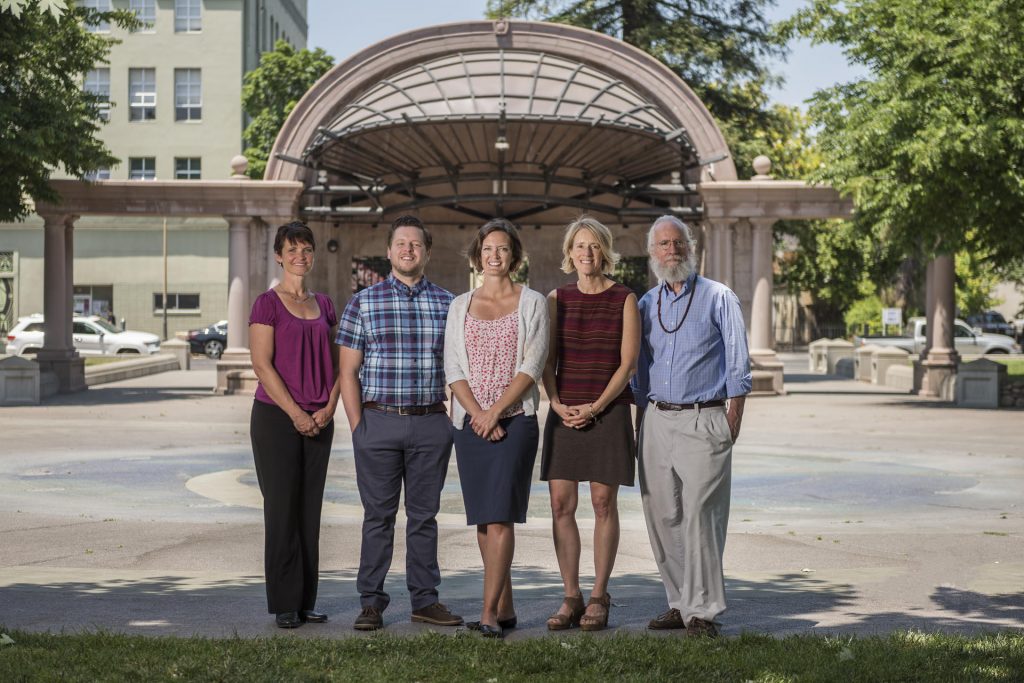

Holly Nevarez, Peter Hansen, Jennifer Wilking, David Philhour, and Susan Roll (left to right), are a group of faculty in College Of Behavioral And Social Science (BSS) that have been researching enforcement of policies related to the homeless and other issues effecting the downtown area, photographed on Wednesday, May 23, 2018 in Chico, Calif. (Jason Halley/University Photographer/CSU Chico)

On the day a team of Chico State researchers gathered to celebrate the conclusion of a lengthy study with a photo in downtown Chico’s City Plaza, an all-too-fitting scene emerged.

Two groups of Chicoans arrived at the park, intending to interface with the unsheltered population there in different ways. On one side, a gathering of acquaintances who decided to begin lunching together to “take back the plaza” from those experiencing homelessness. On the other side, a group who responded to the “take back” crowd by offering sack lunches and clothing to those in need.

Everyone, it seems, wants to reduce the homeless presence in Chico. Where people differ is in their motivations and methods for achieving that goal.

Amid a nationwide homelessness crisis, a group of Chico State researchers, led by political science and criminal justice professor Jennifer Wilking, aimed to shed light on the efficacy of certain policies that affected the unsheltered population. They set their sights on a 5 ½ -year period, examining arrest data as it correlated to the 2013 sit-lie ordinance passed in Chico.

Researchers from five other disciplines including Susan Roll, social work, David Philhour, psychology and social sciences, Peter Hansen, geography, and Holly Nevarez, health and community services joined Wilking’s efforts. The team aimed to explore the arrest records stemming from sit-lie, and to examine the ordinance’s cost to the police department. These findings, based on extensive public records research and more than 50 sources, published as “Understanding the Implications of a Punitive Approach to Homelessness: A Local Case Study” in the peer-reviewed academic journal Poverty & Public Policy.

“Many universities are trying to move in our direction,” said Wilking, who was excited to provide information that could potentially be used in civic policy-shaping. “A surprising number of people feel college education isn’t relevant or useful anymore, and that’s up to us as faculty and researchers to do research that speaks to community needs and helps us move forward with social problems.”

Her goal with the study was to provide data demonstrating how well one approach to addressing this societal crisis would work. Communities across the nation are experimenting with myriad options, ranging from “housing first” models and tent cities to loitering laws and right-of-way restrictions.

Simply called “sit-lie” locally, Chico’s ordinance declared it illegal to sit or lie on sidewalks or in downtown building entryways or alcoves. The University team’s study examined a six-year range, from 2010–16, with the 2013 passage of sit-lie splitting the period. After its 2016 expiry, the outgoing city council re-implemented the ordinance.

While supporters of sit-lie argue the ordinance intends to address behaviors, and not specific populations, its opponents argue it inherently targets and punishes those experiencing homelessness.

Wilking’s study focused on three primary areas of sit-lie arrest records: the number of ordinance-related arrests, the locations where sit-lie police encounters were occurring, and a cost analysis of police response and enforcement.

With sit-lie in effect, arrest numbers rose, though Wilking pointed out that correlation does not necessarily indicate causation.

“We estimated and argued that there were more arrests due to sit-lie, but of course that’s a limitation because it’s an assumption,” Wilking explained. “It may be that arrests were rising anyway, and may not be causal.”

The report also showed that geographical areas of arrest involving people experiencing homelessness began trending northward, indicating the sit-lie ordinance effectively moved those individuals out of the city center—but into other parts of Chico. Finally, the study determined the city cost of policing this population—not including county resources, like jail time or citation collections—was about double what police budgets had estimated.

“We’re incredibly lucky to have the gift of objective University research here in our own town,” said Chico vice-mayor Alex Brown (Psychology, Multicultural and Gender Studies, ’13; MA, Social Work, ’15), elected to the City Council just days after the reinstatement of sit-lie in November 2018. “I feel strongly that we should trust what the data tells us and trust the experts who collect that data.”

Yet many of sit-lie’s advocates—in particular, business owners in the Downtown Chico Business Association (DCBA)—don’t see the ordinance as punitive at all.

“My focus is on conduct, not status, of people. That’s why we see sit-lie as something that can be of benefit,” said DCBA Executive Director Melanie Bassett (Social Welfare, ’74; MS, Corrections, ’76).

But statistically speaking, business owners actually don’t appear to find sit-lie effective, despite vocal support for it in political arenas. A post-study poll conducted by Nevarez and cited in the study suggested local merchants did not report a “significant reduction in problems they associate with the homeless population” through sit-lie’s duration.

Either business owners didn’t notice sit-lie enforcement working, or it wasn’t solving the right problems in the first place.

“The reality is that a lot of this isn’t a police problem. They’re getting called out for things that aren’t behavioral,” Bassett said. “A homeless person sitting on a bench downtown isn’t hurting anyone, and there’s nothing wrong with it. That’s not criminal, and it’s not a reason to call the police.”

One major lesson Wilking learned from objective, community-based research was one she hadn’t necessarily anticipated: Her group’s study being interpreted and used—or not used—to support competing policy ideas.

“We picked a very political issue, maybe not realizing it, and whether it’s ignored or used has fallen largely along ideological lines,” she said. “But my position has been to meet with anybody and discuss the social science itself. How we use probabilistic research depends on those conversations.”

Wilking said the research on arrest data related to sit-lie will continue following its November reinstatement.