Crossing Borders: One Student’s Journey

Forensic Anthropology graduate students Heather MacInnes, 33 (left) and Martha Diaz, 24, (right) work on human bones Human Identification Laboratory on Thursday, July 21, 2016 in Chico, Calif. The Human Identification Laboratory provides forensic anthropology services to state and federal law enforcement, medical examiners and attorneys. These services include search and recovery of human remains, skeletal analysis for the purposes of identification and trauma analysis. (Jason Halley/University Photographer)

Story by Nicole Williams

Originally published in the Chico Statements spring 2017 issue.

Martha Diaz rarely sees “flesh bodies” at the CSU, Chico Human Identification Laboratory, she said in the matter-of-fact tone of a seasoned scientist.

The human remains she processes are often the aged white of weathered bone—years, decades, or even centuries old. If any flesh remains, it is usually highly decomposed, devoid of the familiar characteristics often associated with the human body.

It was different when she arrived last summer at the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner (PCOME) in Tucson. Arizona’s only fully accredited ME office is an hour north of its largest border city, Nogales, which sits on the eastern half of the state’s 378-mile stretch of US-Mexico border.

Every year, men, women, and children from as far as El Salvador and Honduras leave their families and travel thousands of miles through the desert, hoping to cross into the US through Arizona. Since 2001, more than 2,700 migrants have been found dead alongside the state’s rural highways and remote roads, or in the cities and small towns within PCOME’s 10-county service area.

They are classified in PCOME annual reports as “undocumented border crossers”—foreign nationals who die attempting to cross into the US without permission—and make up about 5 percent of the office’s cases.

The route they walk cuts through more than 100,000 square miles of the hot, sparse, and unpredictable Sonoran Desert. Temperatures often exceed 110 degrees in summer, causing hot air to collide with atmospheric moisture to produce violent thunderstorms and monsoons, which can cause temperatures to drop 50 degrees or more in a matter of minutes.

Many migrants die of exposure and hyperthermia, like 19-year-old Elma Vasquez Tomas, who was found south of Highway 86 in the heart of the Tohono O’odham Nation. Some drown, like 30-year-old Luis Noel Orrales Jimenez, who was found off the rural San Juan Ranch Road more than 25 miles south from the nearest town. And others are left unfound for too long, their skeletons leaving no clues to who they were, how they died, or what family might be looking for them.

During Diaz’s internship in June 2016, when new bodies came in with flesh and facial features intact, PCOME forensic anthropologist Bruce Anderson had the Chico State graduate student observe several autopsies conducted by the office’s pathologist to determine cause of death and, if possible, match the body with a name.

“Seeing them fresh like that—I was like, ‘These are people, this happened days ago,’” said Diaz, who sought out PCOME for its unique relationship with Colibri Center for Human Rights, a family advocacy organization in Tucson that collaborates with the medical examiner’s office to identify and return home the bodies of missing migrants.

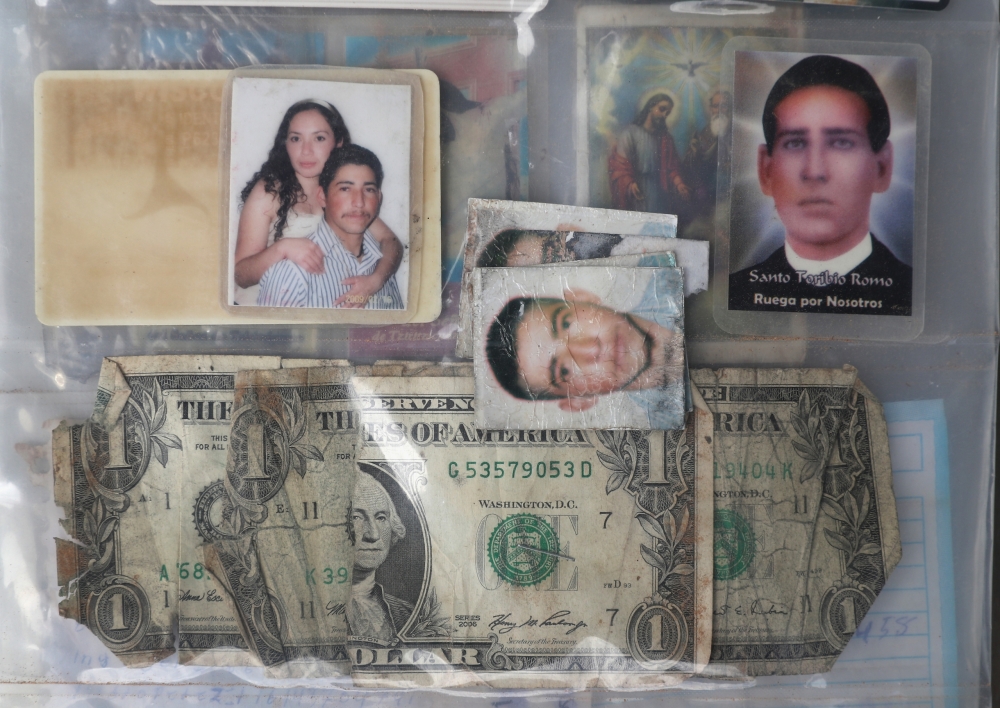

“If they couldn’t be identified by fingerprints or something like that, then that’s when they went to the forensic anthropologist so they could do a report on them—age, sex, ancestry, and all that,” Diaz said. “[Anderson] taught me everything they did. The types of photographs you needed to take. I learned how important tattoos are. We would also get to look at the personal effects that came with the individual.”

One case stuck out to Diaz—a man who carried a paper in his pocket. A picture drawn in a child’s hand. “It’s sad. Because what if that would have been my dad?” Diaz said, her scientist’s voice intensifying with emotion.

Before her parents officially immigrated to the US, Diaz’s dad crossed the border several times near Tijuana to work and save money to pay expensive fees associated with filing for permanent residency and eventual US citizenship for himself and Diaz’s mom.

For the first time in her forensics career, Diaz says she connected with the people she examined—and their families.

“Sometimes I think you can get lost in the forensic world and just be very focused on what’s at hand,” she said. “But this reminds me that we’re doing our work for a purpose. This is helping someone. We can help people, even when they’re deceased, find peace or help them go back to their families.”

Recording Their Stories

As a graduate student in anthropology, Diaz has been trained to search for, recover, identify, and analyze trauma and pathology of human remains by some of the world’s leading physical anthropologists, including Professor Eric Bartelink, president of the American Board of Forensic Anthropology and director of the CSU, Chico Human Identification Lab.

Chico State is the only university in the country—and perhaps the world—to have three board-certified forensic anthropologists on its faculty. Students help Bartelink and Professors Colleen Milligan and P. Willey assist local and federal agencies with more than 70 significant cases each year, ranging from high-profile missing persons investigations to analyses of human remains from archaeological sites.

“For me, the forensic anthropology was just very—it’s science to me, it’s what I do,” said Diaz, who split her internship between the PCOME forensics lab and Colibri Center, where she worked with cofounder and cultural anthropologist Robin Reineke, speaking with dozens of family members hoping to find their missing loved ones.

“Colibri was actually the harder part for me,” said Diaz, who is fluent in Spanish and conducted phone conversations with siblings and parents who were filing reports through the center’s Missing Migrant Project.

At colibricenter.org, families can report a missing person or scroll through stark photographs taken by PCOME in an effort to identify the dead. Photos include close-ups of tattoos, some rippled from rehydrating the skin. A single gray sneaker, covered in mud. A hair tie with two red beads on either end. A faded prayer card. Jacket patches and distinctive dental work.

Diaz remembers one woman who called looking for her husband.

“Then two weeks later you get the remains and you’re like, ‘This might be the guy,’” she said. “It’s just unfortunate because what if Border Patrol would have gotten to him? Or what could have happened differently? When the family called, was this person alive?”

Sometimes families were calling to check on cases that were years old.

“We would call them and they’d say, ‘Thank you for not giving up hope. Everyone else has lost hope, but he’s not just anyone—he’s my grandpa’ or ‘he’s my dad, he’s someone to me,’” she recalled. “And that just broke my heart, because they’re not giving up, and they know more likely than not these people are deceased but they want them back.” Anderson says migrant deaths used to be a rare occurrence in Pima County—none on record in the ’80s and about 12 each year in the ’90s. Shortly after he joined PCOME in 2000, families started calling the office.

“I remember one family—they were sure that their loved one was dead because it happened in front of a friend who had told them. And it didn’t happen in Arizona. But the family needed to report it to somebody,” he said. “Once you have a family that you sense is desperate to tell their story, it’s hard to turn them away, even if you know there is no help.”

Caring for the Dead

Reineke says the increase in the number of migrants dying in Arizona’s desert can be linked to several factors, including the construction of militarized walls along safer urban crossings in Texas and California—like the Tijuana route once used by Diaz’s dad. As a result, more people cross through Arizona’s desert.

Despite the risks, she says migrants continue to flee their home countries due to violence and extreme poverty and to secure employment in the United States—if they can make it. She adds that little has been done to address the increase in deaths along the border because migrants are often portrayed as threatening and there is widespread lack of awareness of their suffering.

At PCOME, Anderson asked his colleagues what he should do about the calls that kept coming. They suggested he refer them to law enforcement.

“It became clear that they wouldn’t—or couldn’t—talk to police,” Anderson said. “And if the police weren’t going to take the reports, someone needed to.”

So, he created a one-page form to collect information that pathologists and forensic anthropologists would need to make an identification—name, country of origin, evidence of injuries or fractures, tattoos, scars, distinctive dental work, date of disappearance, and other key questions that Colibri Center staff and interns like Diaz still ask families today.

Anderson noted it’s not typical for a forensic scientist like himself to talk with families. It took an emotional toll.

“I didn’t know how to get a mother off the phone who wanted to tell me about her daughter’s personality or the tone of her laugh,” he said.

But he kept taking reports, until he met Reineke in 2006. She was a PhD student at the University of Arizona, where Anderson taught. Together, they formed the Missing Migrant Project at PCOME.

“I remember being struck by both how exhausted he seemed and how calm he seemed at the same time,” Reineke said. “I think [Anderson] recognized he was in the midst of a mass fatality situation that was unfolding over time and harming a lot of people.”

For seven years, Reineke says she worked out of a small space in the ME’s office, “connecting the dots between the unidentified dead and the missing” by creating an information-sharing channel between reports she took from families and data collected by PCOME.

One of her first tasks was to carefully review and digitize paper records that Anderson had for years collected and filed away in three-ring binders.

“These are real, irreplaceable human lives that we’re losing every day,” said Reineke, who cofounded the Colibri Center in 2013 to expand the Missing Migrant Project and create a more comprehensive effort to end the “unprecedented loss of life occurring across the border.”

In 2009, Reineke says she was reviewing notes from PCOME describing an unidentified border crosser—a man who had been carrying a dead hummingbird, known as colibri in Spanish.

“Maybe this man found the bird on his journey, maybe it was given to him—but he had this beautiful creature in his pocket,” she said.

She says the hummingbird is a powerful symbol of hope, resilience, and strength and is seen in many indigenous cultures as a messenger between the living and the dead.

“And that’s how we see our role at Colibri—as a messenger to help families with the information they need to heal and as a messenger to policymakers that we have a human rights crisis on the border,” Reineke said.

The Road Ahead

Diaz says the partnership between Colibri and PCOME is instrumental in connecting forensic science to cultural anthropology, government entities to nonprofit agencies, law enforcement to human rights advocates, and individual suffering to social consciousness.

“Being down there—that’s the reason I got into this field of study,” she said. “It really woke me up again to why I came here in the first place. They are making a difference.”

PCOME also partners with Human Borders, Inc., which manages a system of water stations in the Sonoran Desert to prevent migrants from dying of dehydration and exposure, as well as the Arizona OpenGIS Initiative for Deceased Migrants, which provides searchable maps and downloadable data related to migrant deaths in the PCOME jurisdiction.

Every summer, there is a notable uptick in migrant deaths. During Diaz’s internship in June 2016 alone, 25 deceased border crossers were found—nearly a third of the 85 found that summer. Since 2001, an average of 160 people have died each year near Pima County.

“We are on the phone every day,” said Reineke, whose office has more than 2,500 unsolved missing migrant reports. “We speak with relatives of the missing, recording little details about an individual—‘He got a scar cutting a coconut.’ ‘They have three missing teeth on the upper left side.’ ‘She had a butterfly embroidered on her belt.’”

As Colibri Center staff and volunteers document every detail about the missing, Reineke says forensic anthropologists are doing the same for the dead—carefully examining and recording every single surface of bone, every piece of clothing, and every item they carried with them.

“It’s an act of care,” she said, “It’s an act that contests the way immigrants are talked about right now, which is as a massive identity rather than individual people who are loved and cannot be replaced.” There were many challenges for Diaz, who saw herself, her parents, and her life in the stories families told.

“Sometimes you would feel like, ‘Can I do this every day? Is this the right thing to do? What am I doing? Should I be out there looking for people?’” she said. “But I also realized there’s a need for the work that I do. People think, ‘OK, they’re dead, that’s the end of the road, nothing else can be done.’ But I think they’re wrong. So much more can be done. They can be returned. You can use them to be like, ‘Look. This is happening, these people are dying, we need to do something about it.’”

When Anderson began collecting information from families more than 15 years ago, he thought the numbers would attract national attention and cause legislators to create new policies.

“But that hasn’t happened,” he said. “The way to look at it, the way to change it, is to look at one case. People are going to have to take the time and click on one of those dots on the map.”

As the daughter of a border crosser who made it, Diaz says most Americans aren’t confronted with the reality migrants live every day.

“These people are coming here because they are unemployed and they can’t support their families,” she said. “They’re living the struggle every single day. This is their only way out. This is their only way to save their families.”

For Diaz, her internship reminded her why she was first drawn to anthropology as an undergraduate.

“It allowed me to find my voice,” said Diaz, whose forensics studies have also sent her to Mexico, Israel, and Romania. “I felt like I was always in an identity crisis because I have my parents with Mexican culture and my US culture—and you feel like, ‘Who do I belong to?’”

As a first-generation American, first-generation college student, and woman of color in a male-dominated field, Diaz was not always certain of her place in the world.

“Sometimes when you feel down, you’re like, ‘I’m not going to make it,” said Diaz, who will be starting a PhD program at UC Berkeley in the fall. “Dr. Milligan or Dr. Bartelink were the ones who got me back up, saying, ‘You got this, you’re going to be OK.’ I want to be able to be that person for somebody else.”

Reineke and Anderson both see Diaz as the future of anthropology—one they hope will continue to integrate the discipline’s cultural mission with physical science work.

“There’s often a wall we construct between forensic work and grieving families—on one side there’s me, a forensic anthropologist, and on the other there is Robin [Reineke], a cultural anthropologist,” Anderson said. “Martha may be one of those rare individuals that can go back and forth.”