Mapping Lab Takes Closer Look at Population Displaced by Camp Fire

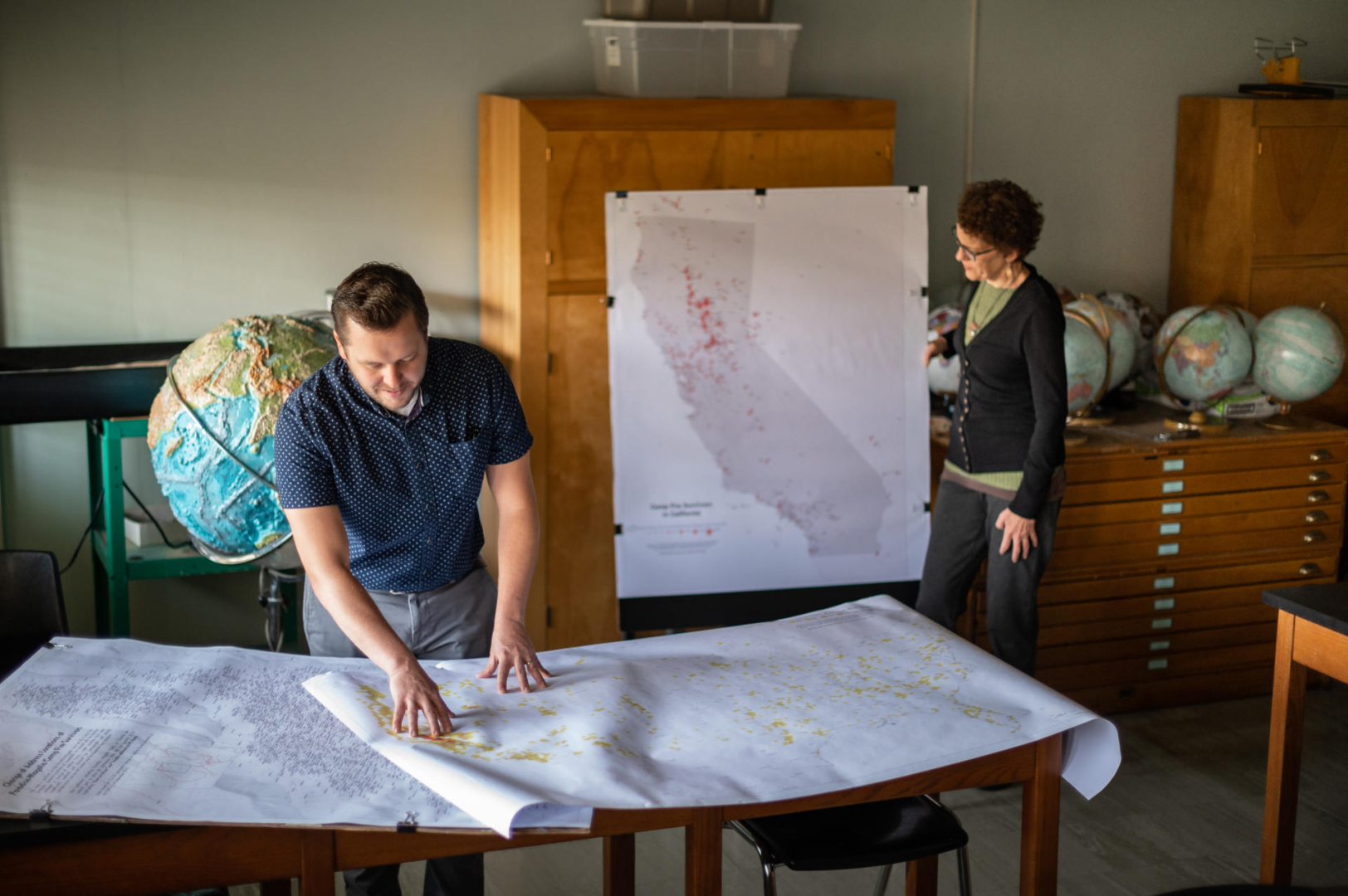

Jacquelyn Chase (left) and Peter Hansen (right) are photographed on Friday, October 30, 2020 in Chico, Calif. The two have been working on research that shows where former Paradise residents went after their town was incinerated in the Camp Fire in 2018. (Jason Halley/University Photographer/CSU, Chico)

Two years after experiencing extreme loss in the Camp Fire, survivors continue to settle into new homes across the country—with nearly 1 in 10 living in zones with high potential for new fires, research shows.

A team of Chico State researchers has been studying the initial movements of those displaced by the blaze, as well as where they are now. Their findings, they say, are revealing.

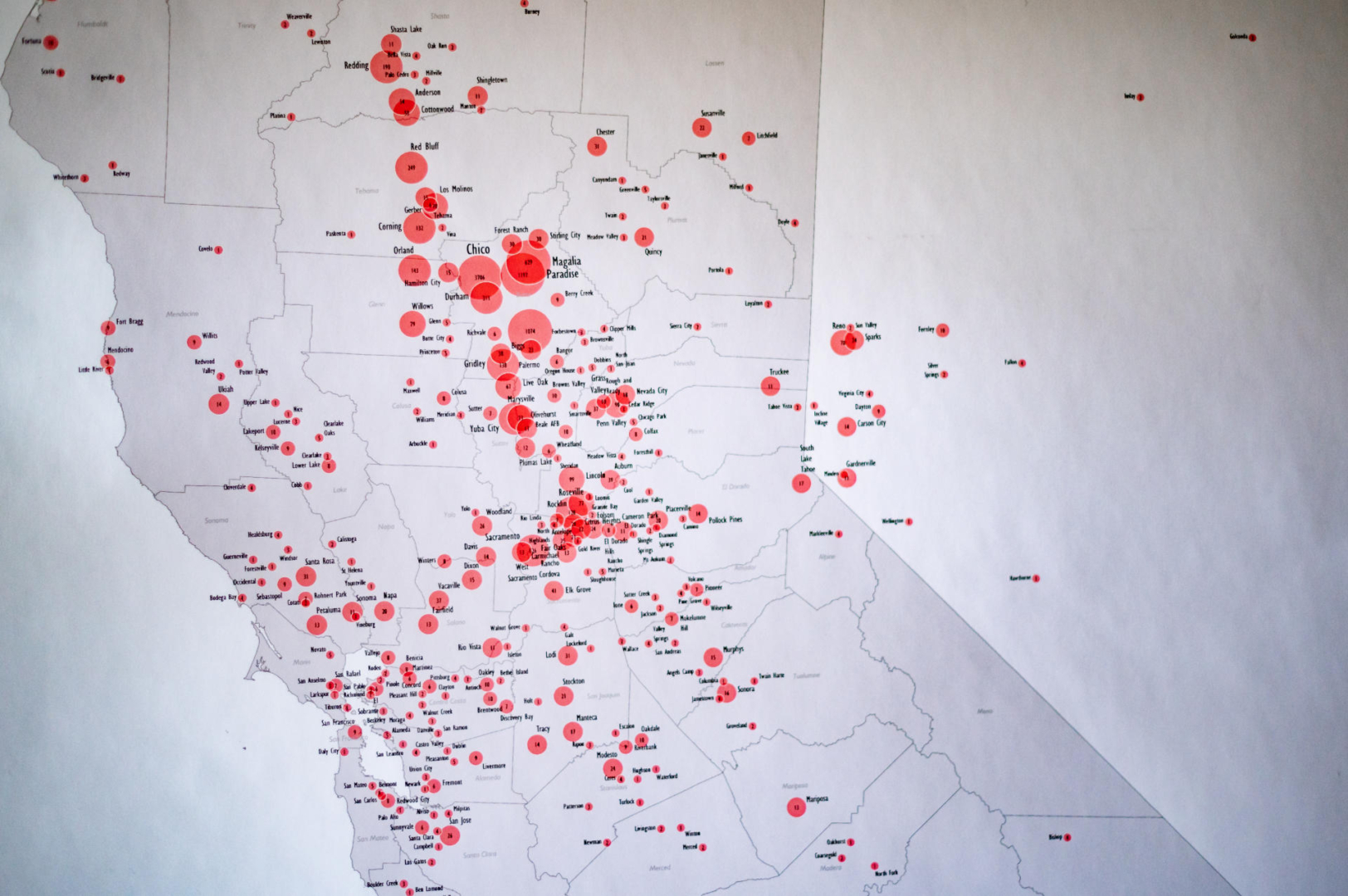

Using data collected by the team, geographic information system specialist Peter Hansen produced “Mapping a Displaced Population” at the one-year anniversary. Media outlets around the country clamored to know more about their findings, which examined trends in where people had relocated based on age, socioeconomics, home value, and if children were part of the household.

As the deadliest and most destructive fire in state history, it seemed there was much to learn from the Camp Fire—and there still is, Hansen ((Geography, ’06; MA, Geography, ’12) says. Since that first analysis, he has continued exploring other impacts with geography and planning professors Jacque Chase and LaDona Knigge, and Economics Department chair Pete Tsournos through the University’s GeoPlace Mapping Lab. Of particular interest is understanding where those displaced by the Camp Fire have moved—distinctly if it once again is in a different (or the same) wildland-urban interface (WUI).

Soon after the Camp Fire, GeoPlace gathered data related to mailing addresses of 37,198 adult-aged individuals who fell within the Camp Fire footprint in October 2018 —which included the communities of Paradise, Magalia, and Concow. Through a USPS change-of-address query, the researchers eventually acquired 13,153 new mailing addresses for those residents. Overlaying these new addresses and a US Forest Service Wildfire Hazard Potential dataset, which maps the national potential for wildfires from very low to very high, Hansen noted that 9 percent of the new mailing addresses were in a “high” potential zone, while an additional 5 percent were in a “very high” potential zone—a combined 1,842 individuals.

Additionally, 2,640 of the new addresses—20 percent—were within five miles of a 2019 or 2020 fire perimeter, including blazes such as the Kincade Fire in 2019 and a host of incidents this year, like the Glass, Slater, and Walker Fires. While there are numerous reasons people have remained close to wildfire zones—a desire to live in a less urban area or rebuild in Paradise itself—Hansen and Chase speculate their findings reflect that as wildfires increase in number, acreage and proximity to urban areas, it’s also inevitable that finding a place to live with reduced risk is increasingly difficult.

“When you look at maps of California that are divided up by these regions into high-severity zones, and then these are all wildland-urban interfaces, it doesn’t look like there’s a lot left,” Chase said. “Those maps are extremely worrisome.”

Those maps can also tell a story of who is moving into (or returning to) high-severity fire zones—including Paradise. And when Chase and Hansen view the permanent change of address data, they also see it contains a disproportionate number of homeowners—both before the fire and after—suggesting a bias that favors homeowners (particularly those who are well insured). What’s missing in their new address data are renters.

In a town that once held a housing stock of more than 14,000, just 418 single-family homes have received certificates of occupancy (they have been cleared by the Town of Paradise to be lived in by residents). By comparison, just 70 multifamily units have so far received certificates of occupancy. The research team suggests that insured homeowners can more easily establish a new place of residency (by rebuilding or moving) than those who were renting (and likely uninsured)—the latter looking for affordable homes or apartments in an already tight rental market.

“When I think about this housing bias out there, I’m so sure of it—I’ve read hundreds of articles, and a fraction of them have mentioned anybody but homeowners,” Chase added. “I know it will be a wakeup call.”

Gathering additional data would continue to provide value to this type of research. Hansen and Chase want to explore vulnerability, test their theories on family reunification, and further investigate the role of insurance and how recovery favors homeowners. Though this research will likely yield important lessons, it requires funding that they currently lack—at a cost of approximately $1,000.

Still, they continue their work.

With a submitted journal article on social vulnerability in wildfires currently in review, Chase and Hansen are also collaborating with Colleen Milligan and Ashley Kendell, faculty from the Department of Anthropology and the Human Identification Laboratory, on a chapter about social vulnerability in a publication around wildfire response. They look closely at whether social isolation was a contributing factor in the survivability of the Camp Fire and how mobility (aside from characteristics such as disability, age, poverty) may have played a role in whether individuals survived or not.

From Hansen’s data-collection acumen to their collaboration on papers, Chase said that this model of partnership—faculty publishing with University staff—is quite uncommon. She and Hansen are both grateful for the opportunity to do meaningful work.

Chico State—as well as other universities located near natural disasters—has a responsibility and opportunity to study and research the Camp Fire’s aftermath, effects on basic needs, and human and financial toll because it happened “in our backyard,” Hansen said.

“In a lot of ways, we’re the most appropriate people to be looking at it because we can consider some of the contexts and we know where we may be barking up the wrong tree or where to go for different types of resources because of our local connection,” he said.

Additionally, Hansen said higher education institutions don’t have the same research encumbrances that other entities and agencies may have, with pointed missions, goals, or orders.

“In academia, we have the opportunity to ask different types of questions that don’t need to suit an outcome,” he said. “Sometimes that freedom just fosters more discussion and might lead you to levels of information or detail that weren’t considered before.”