Biology Faculty’s Research Sets Foundation for Future Findings of Life’s Evolution

To unlock the mystery of evolution, scientists must often look in places that resemble Earth’s hostile origins. That’s why, as a graduate student in 2016, Angela Oliverio traveled halfway around the world to study microbial eukaryotes living in the hot, acidic geothermal springs of New Zealand’s Taupō Volcanic Zone.

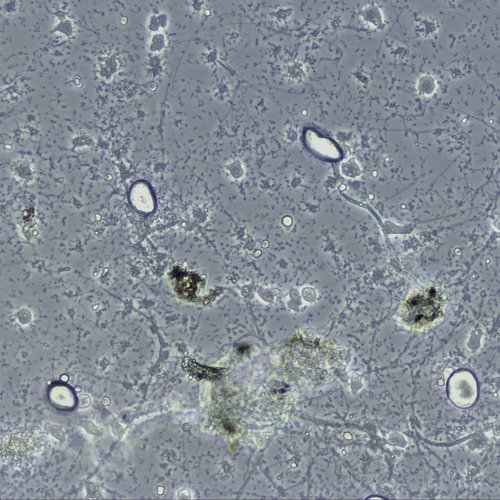

For context, a eukaryote is an organism or cell that possesses a nucleus—just like those comprising animals, plants, and fungi—but most of the eukaryotic diversity is comprised of unicellular organisms such as amoebae and ciliates, collectively known as protists. Most eukaryotic cells cannot withstand high temperatures (over 40 degrees Celsius) and very low pH conditions (less than 2)—which are the ranges where geothermal springs’ uniquely inhospitable environments thrive.

“That multiple independent lineages of amoebae have successfully figured out how to flourish in these environments is incredible,” Oliverio said. “And it brings up an interesting research question—are solutions to the challenge of extreme heat similar, or do different lineages of amoebae have different ways that they have ‘solved’ this challenge?”

*

At the time, one of Oliverio’s inspirations came from findings published by Chico State Biological Sciences Professor Gordon Wolfe, who conducted his research in the acidic waters of Boiling Springs Lake, a geothermal spring in Lassen Volcanic National Park, a decade earlier. Far closer than New Zealand, Boiling Springs Lake is the host of the largest active hydrothermal system in the Cascade Range, a 700-mile mountain range that stretches from Washington to California.

In 2008, Wolfe received a five-year National Science Foundation (NSF) grant and, along with co-Principal Investigators from Portland State University and Cal Poly Humboldt (then Humboldt State), gathered specimens to study microbial diversity in extreme environments. Around 20 Chico State graduate and undergraduate students participated—many year-round—in the research project studying protists found in Lassen’s geothermal springs.

The water of Boiling Springs Lake sits at around 125 degrees Fahrenheit with a pH of 2 (on the pH scale of 0 through 14 with 7 being neutral, the lower the number the higher the acidity)—possibly an ideal setting for an abundance of diverse eukaryotic life.

“Most people who know Lassen don’t even know the lake is there. We chose that location because it’s not well-traveled,” Wolfe said. “It’s a beautiful, colorful place, but the springs themselves are like warm battery acid.”

The grant ran its course, the team pored over the data, and Wolfe’s research revealed that Lassen’s geothermal springs may harbor novel protists—an unexpected and important finding—and others that change their form to adapt to their surroundings. He said their efforts produced eight published articles, one PhD and multiple theses, an educational brochure for the park, and an appearance on a National Geographic special.

*

In 2022, four years after publishing her New Zealand geothermal findings, Oliverio was hired as an assistant professor of biology by Syracuse University. And even as she has moved onto other projects (including completing her PhD), she has not forgotten Wolfe’s findings and Boiling Springs Lake, which she said were incredibly informative to her.

“I’d always wanted to go back and continue to work on the geothermal protists because we still have almost no understanding of how they’ve adapted to these extremely high temperature and sometimes low pH environments,” she said. “So, when I started my own lab group at Syracuse in fall 2022, one of the first things I did was think about how I could start working on these geothermal microbes again.”

Oliverio returned to Boiling Springs Lake in 2023 with her own team (including Wolfe, who showed the visiting scholars locations where he’d previously recovered amoeba) to conduct additional research on the protists and hopefully learn how they have evolved and adapted to this extreme setting. Answering these questions could expand our collective understanding of the types of environments across the universe that may be suitable for life.

“We discovered that several lineages of amoebae were often recovered from extremely high-temperature environments,” says Oliverio. “This suggests that studying those lineages may yield great insight into how eukaryotic cells can adapt to life in extremely hot environments.”

While Oliverio’s protists likely aren’t much different from those collected by Wolfe more than a decade ago, the technology used to test them has certainly advanced. Noting that “often science sits on the first little nuggets of insight until the rest of the field catches up,” Oliverio has superior tools, resources, and equipment at her disposal to see how these eukaryotes survive, evolve, and thrive in their extreme environments.

“The field has caught up with the research and we can use emerging sequencing and bioinformatics pipelines to identify the cellular and genomic adaptations that allow these lineages to flourish,” she said.

That’s how it works, said Wolfe—scientists stand on the shoulders of those who inspired and came before them. He did it with Thomas Brock’s pioneering research from 1978, just as Oliverio is doing with his findings.

“Science and scientific research are a process,” he said. “And with each new breakthrough we inch closer to more fully understanding the world around us—it’s why we do it.”

In publishing their findings, Oliverio and her team re-discovered Wolfe’s work and gave another nod to his research. In the manuscript Oliverio’s team published, Oliverio and her lab research assistant, Hannah Rappaport, asked Wolfe if they could include a photo of the protist Tetramitus thermacidophilius that he found in Lassen nearly 15 years ago. Wolfe gave his hearty approval.

“I’m honored that Angela has been inspired by my work, and I was very happy that she was able to confirm our prior observations of the protists that dominate Boiling Springs Lake,” Wolfe said. “I’m grateful she is using modern methods to advance our knowledge of these amazing organisms and look forward to learning what her genomic investigation reveals about the adaptation of amoebae to extreme environments.”