Engineering for a Better Tomorrow

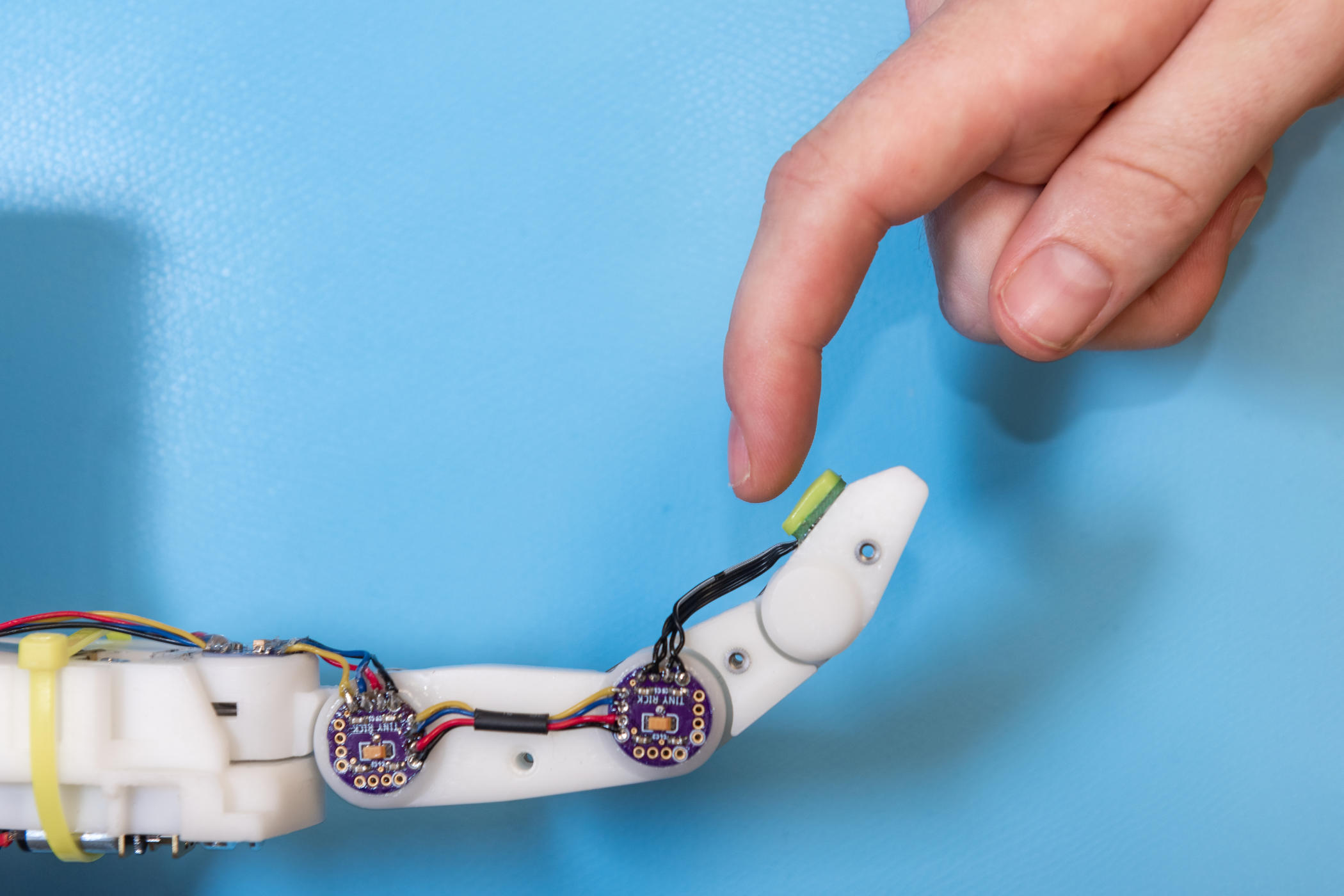

Students work on development of their Telepresence Electromechanical Finger Sensor, which is to be featured in the ECC Design Capstone Expo on Tuesday, December 10, 2019 in Chico, Calif. (Jason Halley/University Photographer/CSU, Chico)

Creating safe drinking water for vulnerable populations. Reducing single-use plastics. Developing technology to quickly build homes in disaster zones.

A year’s worth of work to tackle some of society’s most pressing challenges culminated in a design showcase on campus last week, when students in the College of Engineering, Computer Science, and Construction Management presented their capstone projects. Supported by industry sponsors, the students have worked diligently to design, build, and test solutions to a broad range of challenges.

Senior Ryan Turner, a mechanical engineering major, is already working as an engineer at Sierra Nevada Brewing Co., and will be continuing his career there after graduation. It was only natural, he said, to take an idea he had and see if students could make it a reality.

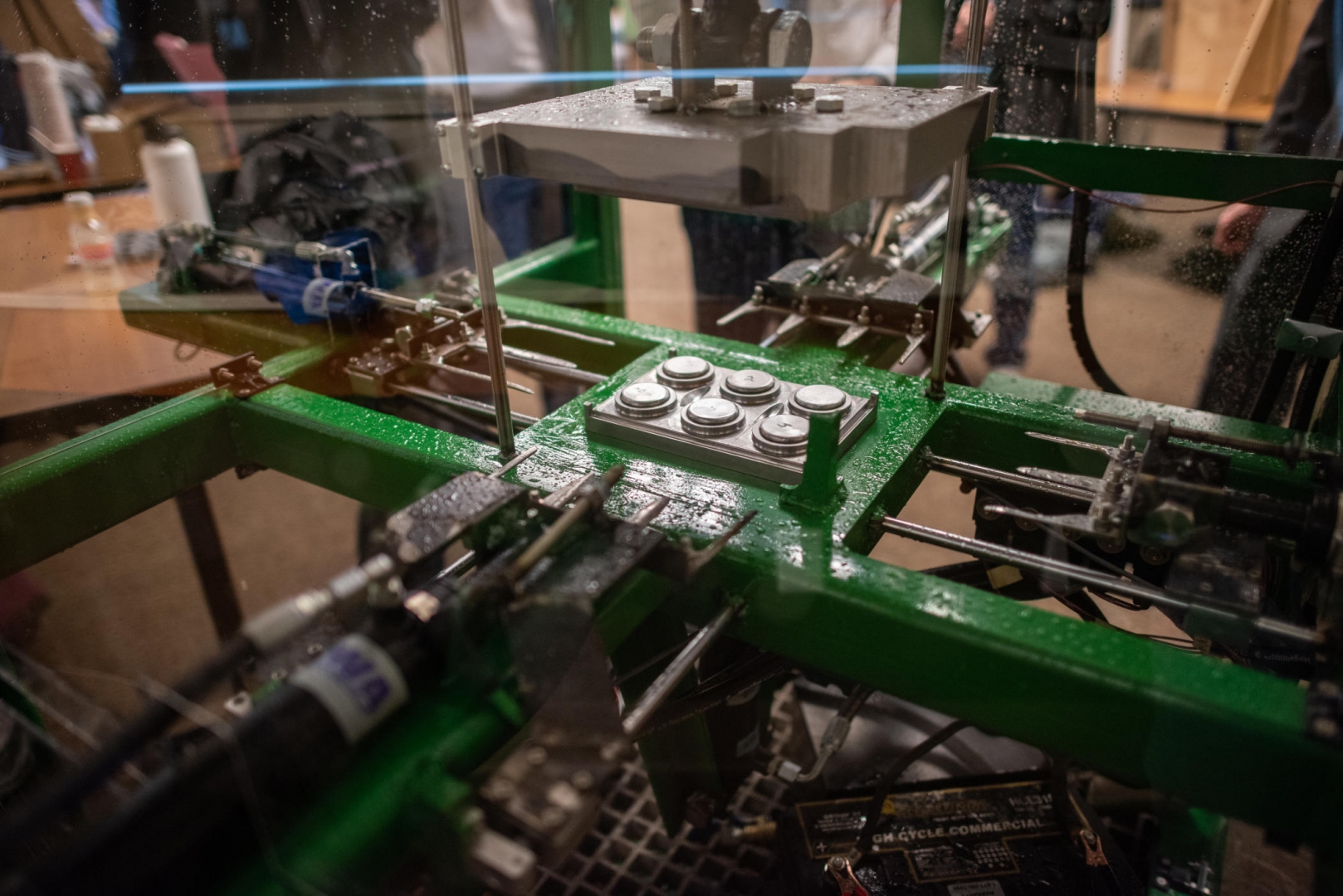

His team was tasked with creating an aluminum holder for a six-pack of beverage cans. While many beverage producers have moved away from the traditional plastic ring holders, their alternatives—cardboard boxes and solid plastic holders, which are often made from single-use—have their own environmental and cost detriments. Conversely, aluminum has nearly infinite recyclability and an actual value by manufacturers and recyclers that encourages reuse, Turner said.

He ultimately hopes the students will be able to patent their product, which includes both the six-pack holder and the machine to make it.

“It’s never been done before, so that’s really exciting,” he said. “We are doing something truly innovative. The nature of this entire project is creating something from nothing.”

Supply chain issues plagued the team during the last few critical weeks, which delayed the arrival of critical parts and forced them to sacrifice some product testing. They consider what they presented at the expo to be a first-generation prototype, and Sierra Nevada Brewing Co. will now take their idea and continue to refine and optimize it, which is incredibly exciting, Turner said.

“If this becomes a success and is the next generation of beverage packaging, all five of us will have had a hand in its creation,” he said.

Another group of mechanical engineering seniors was equally thrilled to unveil their end product: a 3-D printer that can quickly build homes out of concrete. Unlike other building materials, concrete has a minimal expense, meets local housing codes, can be completed in less than 24 hours, and is fire resistant.

As students led demonstrations, they explained how affordability was among its key advantages, as the machine itself costs less than $10,000. Set onto a frame standing nearly 12 feet high, a central arm led the concrete nozzle methodically in the strategic patterns it would use to frame a house.

The technology already existed but none of it was in practice in the United States, nor was it affordable or up to US building standards. So the students developed everything from scratch, using existing computer animation and game development models as a launch point.

Senior Mat Benavidez, a mechanical engineering major, said the team sought out faculty as experts for advice from motors and vibration to concrete—which had perhaps the steepest learning curve. They mixed up more than 50 trials over the summer to find the perfect blend, which included silica and nylon to help with structural integrity.

“I feel like I learned so much this year. It’s just such a vast project,” he said. “It’s a culmination of everything we have learned, and then some.”

As he aspires to be a design engineer, he appreciates that this project, perhaps more so than any other he has worked on to date, has the power to change people’s lives. While first envisioned to address housing solutions in the wake of the Camp Fire, it could be a solution to disasters worldwide.

“It’s the first project that can make an impact,” Benavidez said. “I’d like to see it take the next step and actual result in homebuilding. Maybe we can work with the next group of students to pass the torch and grow the technology.”

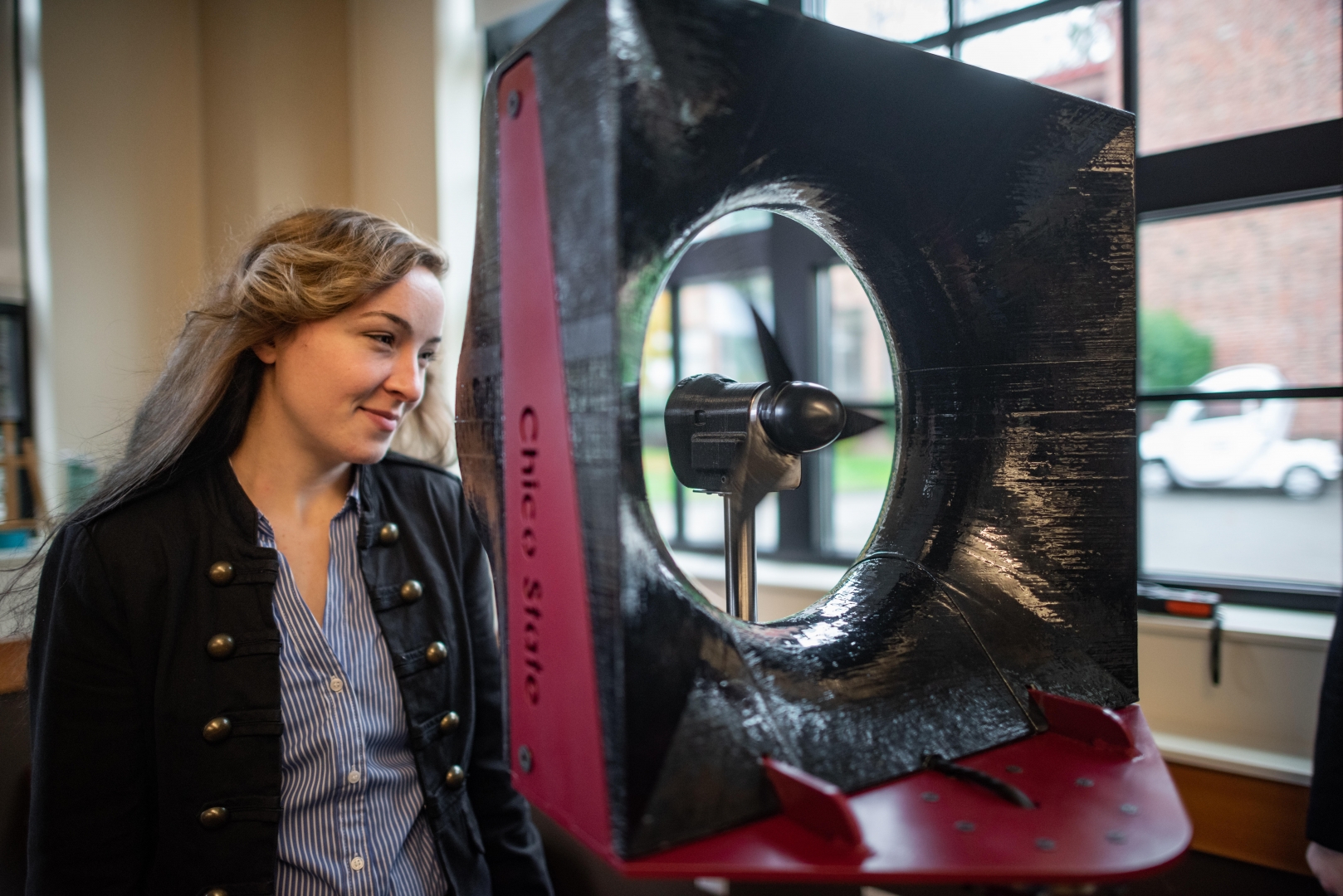

Senior Erica Plasencia’s group was already taking an existing concept to new levels. While previous students had focused on wastewater treatment, the civil engineering major explained that their two proposals addressed a sustainable drinking water system for the Lake Atitlan Basin in Guatemala, where more than a quarter of a million people are living with dangerous water quality because of the presence of arsenic, cyanobacteria, pathogens, algae, and other contaminants.

They began their project with the goal of creating a slow sand filter facility, which would be simple, cheaper to build, and more affordable to maintain over time. However, as additional data was shared by their Guatemalan contacts about the degree of contamination in the water, especially arsenic, they realized they needed a better facility, Plasencia said.

It helped to think about the actual people in Guatemala they would be helping, including the financial impact those citizens would personally experience by the cost for a solution. An extra cost of $150 per person per year could make the entire project out of reach.

“It made me realize how important engineering is overall,” she said. “This project takes all that I’ve learned into account and solves a problem for people.”