Inside the ‘RAD-Lab’: Looking to the Ground for Solutions

There’s not much in the world older and more important than soil.

Since the days of hunting and gathering, soils have been critical to the survival of human civilization, producing diverse ecosystem services and about 95 percent of all food grown.

Soils connect us and their layers provide an ancient and contemporary canvas for students and faculty to investigate some of the most pressing topics of our time, ranging from food security to climate change.

The Regenerative Agriculture Demonstration Lab, otherwise known as the RAD-Lab, is the brainchild of Garrett Liles (Interdisciplinary, ’02), a professor in Chico State’s College of Agriculture.

What began as an idea in grad school has become a service lab where soil health and food nutrient density assessments happen across applied research projects. This in turn supports the Center for Regenerative Agriculture and Resilient Systems’ efforts to help farmers implement regenerative agricultural practices like cover cropping, grazing, compost application, and tillage reduction.

Years ago, Liles realized that a key limitation to understanding soil health and soil carbon was a lack of labs and access to affordable data. “Understanding carbon or soil health is too expensive for most farmers,” Liles explained. “There are plenty of labs that provide nutrient analysis to support fertilizers but none to track soil health.”

After joining the University as a faculty member in 2015, he started to envision an environment where this work could be done, and students could gain important experience and skills. The focus has always been increasing access and reducing the cost to become a resource for the North State agricultural and natural resources community who want to know about their soil.

In 2017, funding through a cooperative agreement with the National Resources Conservation Service to research soil health in our region and the availability of an old greenhouse allowed Liles’ idea to become a reality. The greenhouse (known as the soil processing area, or SPA) was transformed into a research space to process soil and perform basic analysis.

Simple by design and DIY in nature, the SPA has a workshop-meets-science-lab feel with a mix of basic tools, safety gear, and well-organized equipment across multiple workstations.

“This gave us a space to handle and process soils and was the first step in the process of building infrastructure and getting the equipment we needed. From here, we’ve expanded to a couple of spaces in Plumas Hall (the home of the College of Agriculture) and added analytical capacity to assess soil health,” Liles said.

Now in its 6th year, the RAD-Lab is hitting its stride. Currently staffed by a lab manager, three staff researchers, and a growing roster of student employees, it serves farmers, community partners, and anyone interested in growing healthy, nutrient-rich food using regenerative-climate smart practices.

Against the backdrop of California’s agricultural heartland, this venture presents a giant opportunity to contribute to the long-term vitality of our region and nation. Part of its fiber and DNA is a focus on providing students opportunities to work and build skills through experiences that cross sampling, processing, and analyzing samples and thinking about professional life and the importance of soil.

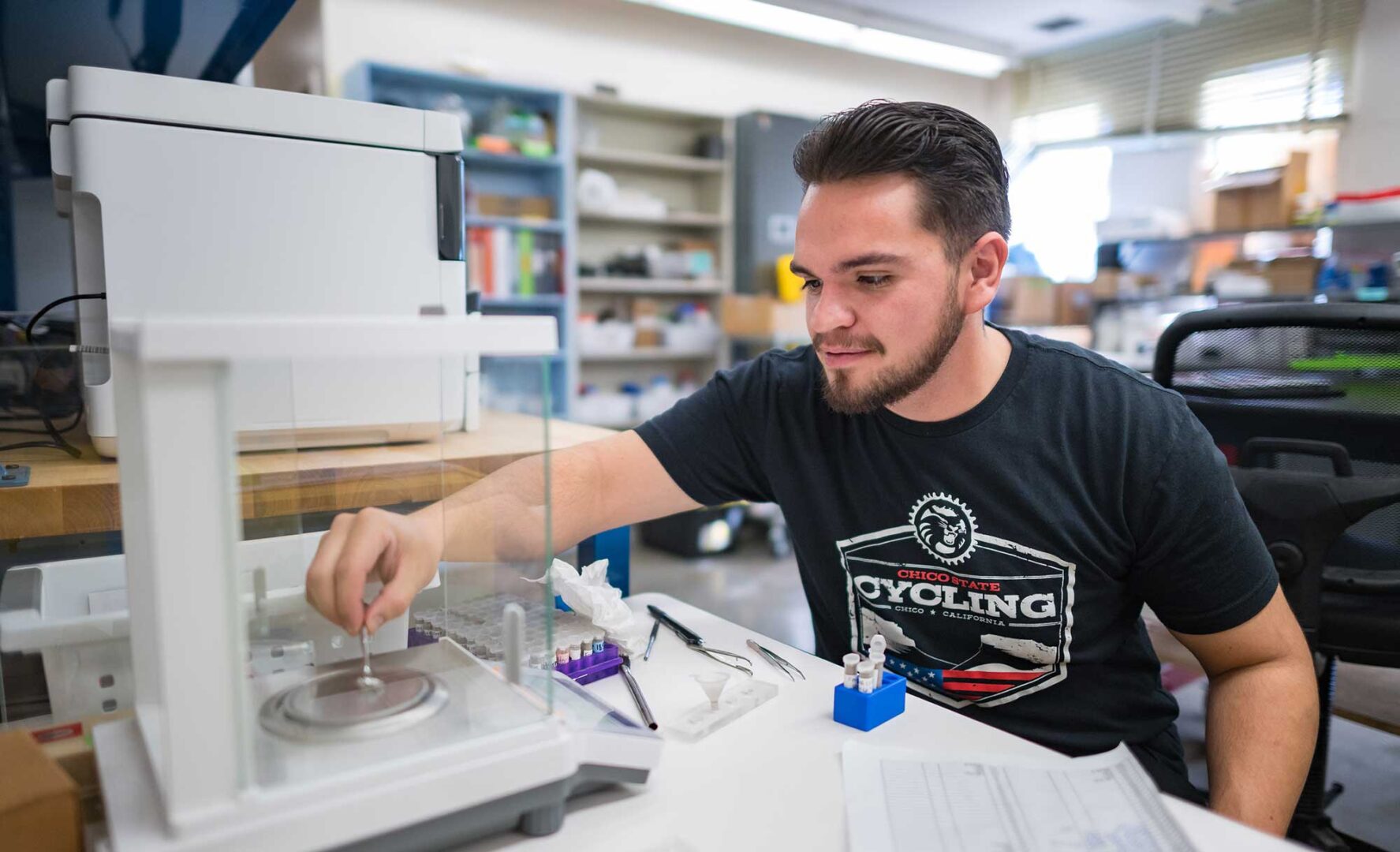

“What drew me to the RAD-Lab was the regenerative soil aspect of it—making sure that we’re able to produce food in the future,” said Alex Woodward, a junior majoring in plant and soil science. “It can be pretty tedious. A lot of what we do is measure and weigh out carbon and nitrogen, but those are the building blocks of plants. And that’s how we’re able to make sure there’s more fruit on the trees, more corn can grow, and future generations will have access to food.”

On one hand, the assessments are intended to help promote healthy soil and sustainable growing practices, which equate to healthier crops and associated ecosystems. On broader levels, the data they generate help show the benefits of regenerative-climate smart agriculture practices—while simultaneously helping growers develop comprehensive carbon farm plans, access incentive funding to install additional practices, and enter carbon markets or other emerging ecosystem services markets. At the end of the day, regenerative-climate smart ag helps farms become more resilient in the face of a rapidly changing environment and the need to feed a growing world.

Liles’ long-term goal is still firmly connected to the original problem he identified. “We want to create something that’s easy to reproduce and copy. Outside of the space, everything we’ve purchased is from hardware and restaurant supply stores. We want to show that we’ve used equipment that is inexpensive and widely available. Farmers, urban growers, and anyone else interested in soil health can do this,” Liles said.

Alongside the lab work being conducted by students, the team is creating video tutorials, process documentation, and tracking workflow data and information. Liles imagines a simple cookbook that someone can use to create their own lab that measures carbon, soil health, and more.

“I’m hoping that in my career, these pop-up smaller labs that focus more on soil function and measure basic soil properties are geographically distributed,” Liles said. “But what I mainly hope comes out of this is that people start to think about soil. Even if it’s not every day, people should understand that soil connects us all—if we want to eat, we need to protect it.”

This hope is being reflected on campus, as the RAD-Lab continues to draw interest from students—even those who are new to the wonders of soil.

“Soil was not my first interest, but I’ve grown here and learned a lot from my staff colleagues and faculty, who are helping me with opportunities for the future,” said Daniel Rodriguez, currently majoring in plant soil science with an emphasis on crops and horticulture. “I can definitely see a lot of the skills I’ve learned here translating very well to the future for me. Working in the RAD-Lab has given me a different, bigger perspective on soil sciences—how wonderful and vast and important it is.”

* All photos by Jason Halley/University Photographer