Thousands of Physical Maps Need a Home—Students Helped Find One

Seven-foot-tall cabinets sit shoulder-to-shoulder, stretched along the left side of Butte Hall’s Map Room. Hidden within their 100 drawers are approximately 40 maps of varying size, material, location, and age. Maps of varying sizes are stacked flat. A few are ripped here and there, others remain pristine. Larger maps are folded to accommodate the space, while smaller ones take up a fraction of the drawers’ space. Meanwhile, dozens of other maps take up space around the room lying flat or rolled up.

Each one tells a story. Where the roads in 1951 Mozambique and 1962 Germany traveled. The shoreline of Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula—13 years before the state became part of the US. The smallness of 1954 Chico in quainter, quieter times.

“The maps are historical artifacts,” said Peter Hansen geographic information system (GIS) specialist for the College of Behavioral and Social Sciences. “They’re just sitting there, like a time capsule.”

Geography and planning lecturer Steve Herman said this collection of more than 4,000 maps from around the world has long been a source of pride for the Geography and Planning Department—particularly in the mid-1970s.

“It was a real beehive of activity then,” said Herman (Geography, ’79). “Professors were constantly coming in and out and borrowing maps to be used in the classroom for class projects or discussions.”

Over the years, however, as physical maps went digital, academic interest in the map room’s contents waned. And today, with a move from Butte Hall to a new location looming, one of the many questions is what to do with these maps.

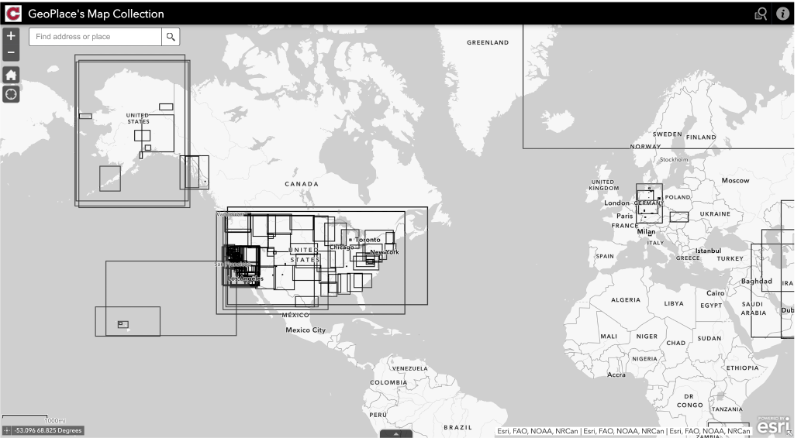

Hansen (Geography, ’06; MA, Geography, ’12) had an idea: Digitally capture the maps, categorize them using metadata, and create a spatial index of the maps to be searchable via a web app so anyone with the link can access the database and digital images of the maps.

Hansen offered the task to student interns at GeoPlace, a University lab that provides mapping and spatial data services for the campus and wider Chico communities. Several students pursuing their GIS certificates jumped at the chance to work on this year-long project.

During the fall 2021 semester, physical and environmental geography majors Anthony Lepori and Lucas Neal and human geography and planning major Matthew Min captured photos of the maps. After Min graduated in the fall, Lepori and Neal were joined by fellow physical and environmental geography major Joanna Vidal during the spring 2022 semester to continue digitally capturing maps and create the spatial index for the web app.

Together, the trio scoured through the map drawers and determined which maps they thought were worthy of archiving and unique in some way.

“It was fun determining what kind of significance each map had,” said Vidal, who graduated this spring. “We asked, ‘where is this from, what’s the time period, could this be helpful in the future to anybody who will eventually look at this digital database?’”

To digitally capture the images of the maps, Hansen and the team looked to arguably the best to do it on our campus—University Photographer Jason Halley. Provided with a loaner camera, tethering cables, lighting gear, and framing supports for the maps, the students were able to vertically hang the maps and zoom the camera in and out—while also physically moving the lens closer and farther away when needed—to get the best shot.

Once the images were captured digitally, it was time to curate the map database. Using a Google Sheet, the students created keywords and a unique ID number for each map. The end result is a web app containing digital records of 425 physical maps the students selected, searchable by metadata, like location, the organization that created the map, and tags. The results of the students’ work provide a glimpse into the past and the importance physical maps once held for different purposes around the world.

Five of the maps captured are at least 100 years old, with the oldest being a 1908 map of the Sacramento Valley from Redding to Suisun Bay created by H.J. Furley. The tallest map measures 75 1/2 inches (a zoning map of Chico from 1968), the widest 67 inches. From the 1950 “China Linguistics Group” map created by the Department of State and the Royal Thai Survey Department’s map, “Monthly Temperatures in Thailand,” from 1937–1960 to Alaska Coachways’ 1949 map “Highways of Alaska” (front and back), this archiving project was an opportunity for the students to put into practice what they were learning from in their studies.

“We have this ‘Cartography’ class, which is about map design, how can one best communicate an idea via data,” Vidal said. “This project completely connected to what we were doing in the classroom.”

Neal said exploring hundreds of maps from the drawers in a seldom-used room and using technology to share them with the world has been extremely rewarding.

“Not only from being able to explore the map room and deciding which maps to look at next, but also in the way that we created our own spatial database and our own web app that anyone can use, regardless of whether they’re affiliated with campus or not,” he said.

Additionally, after two years of remote learning due to the pandemic, the students were grateful to be able to work collaboratively together.

“We were so disconnected for so long, it was great for me to be connected with my classmates and with the department,” Lepori said. “I felt like I was a part of Chico State again.”

For many—not just geographers—paper maps represent different things, whether it’s eliciting a childhood memory, cultivating an interest in travel or landscapes, or reminiscing about how things used to be.

“There’s real value in having a collection of things from the past that are still in good condition that you can see and touch,” Herman said. “You’re able to get some sense of where we’ve come from, where we are now, and, in some cases, looking back with a little bit of sadness.”

With 425 maps now digitally archived, the fate of the physical maps remains uncertain. From a historical perspective, both Herman and Hansen believe the maps are important artifacts and deserve a future—and that they should be cared for and displayed so that others have the opportunity to admire them.

“Why can’t we have a map museum?” Herman asked. “There are museums for so many other things on campus and they’re all wonderful. Now, maybe it’s geography’s turn.”