Pandemic-Themed Class Explores How Science and Society Tackle Germs

A student uses a skeleton hand to pick up plastic balls with velcro as Troy Cline (center) teaches fun activities about antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in his Pandemics, Germs, and Society | (BIOL 311) class on Monday, February 28, 2022 in Chico, Calif. (Jason Halley/University Photographer/Chico State)

As the nation continues to grapple with COVID-19—and learns to live with it—a new course in biological sciences has been one of the timeliest of Professor Troy Cline’s career.

“Pandemics, Germs, and Society,” now in its second semester, provides students with a general overview of bacteria, fungi, and viruses before introducing concepts related to how novel pathogens emerge to cause pandemics. In addition to studying vaccine science, information literacy, and how public health measures can restrict the spread of pathogens, students also become familiar with the beneficial uses of microbes in agriculture, nutrition, and sustainable energy.

“COVID-19 has brought science and viruses and public health front and center to our national conversation,” Cline said. “These issues aren’t going away so we need a pipeline of passionate and skilled scientific minds to answer the important questions about how pandemics occur and how to prevent them.”

Pre-nursing major Steven Verschoor, a junior, said the course takes what he has learned in other classes and gives it a practical application, broadening his understanding overall. He especially appreciates their discussions on facts versus opinions, conspiracy theories, and using research to dispute false claims.

“This class is so interesting considering the pandemic in today’s society,” Verschoor said. “There is a whole societal aspect of the way disease shapes our lives.”

Cline starts the semester with a discussion about the difference between anecdotes and data, and the difference between data and a good scientific study.

“There was so much misinformation, misunderstanding, and confusion at the start of the pandemic—and still is,” he said. “I wanted to help students understand these issues that were in the news and misconstrued either intentionally or unintentionally.”

While biological science fundamentals are an important element of the course, Cline cares more that students finish his class with a clear comprehension of what is valid science and how to discuss topics related to viruses and bacteria within their social circles to inform others on a peer-to-peer level.

“I hope the students will become a good source of information for their friends, families, coworkers, neighbors, etc. to create a more informed citizenry,” he said. “With so much distrust of science, experts can talk until they are blue in the face. Who people need to hear from is regular people who you don’t dismiss.”

Cline tries to make the subjects the class tackles as engaging as possible. Some days, this means using colored beads to represent a population of bacteria with varying levels of antibiotic resistance and how that population will change over time upon exposure to an antibiotic. Later in the semester, he will bring in a selection of foods made possible by microbes. The students can sample yogurt, sauerkraut, kimchee, kombucha, and stinky cheeses as they talk about how there are more good bacteria than bad bacteria in and on our bodies than in the environment, with a positive impact that far outweighs the negative.

One afternoon, several weeks into the semester, Cline offers his students a bag filled with small plastic balls. The white ones represent bacteria, and a plastic grabber they use to pull them out is the antibiotic. As the grabber attaches to little bits of Velcro on the balls, representing the unique bacterial structure of a cell wall, Cline explains how antibiotics can permeate cells to stop them from growing or kill them entirely.

Then he adds orange balls to the mix, representing viruses. When the grabber picks up white ball after white ball, leaving all the orange ones behind, he explains that it reflects how antibiotics only impact bacterial cells—not viruses—which is why antibiotics can’t stop COVID-19 or the common cold.

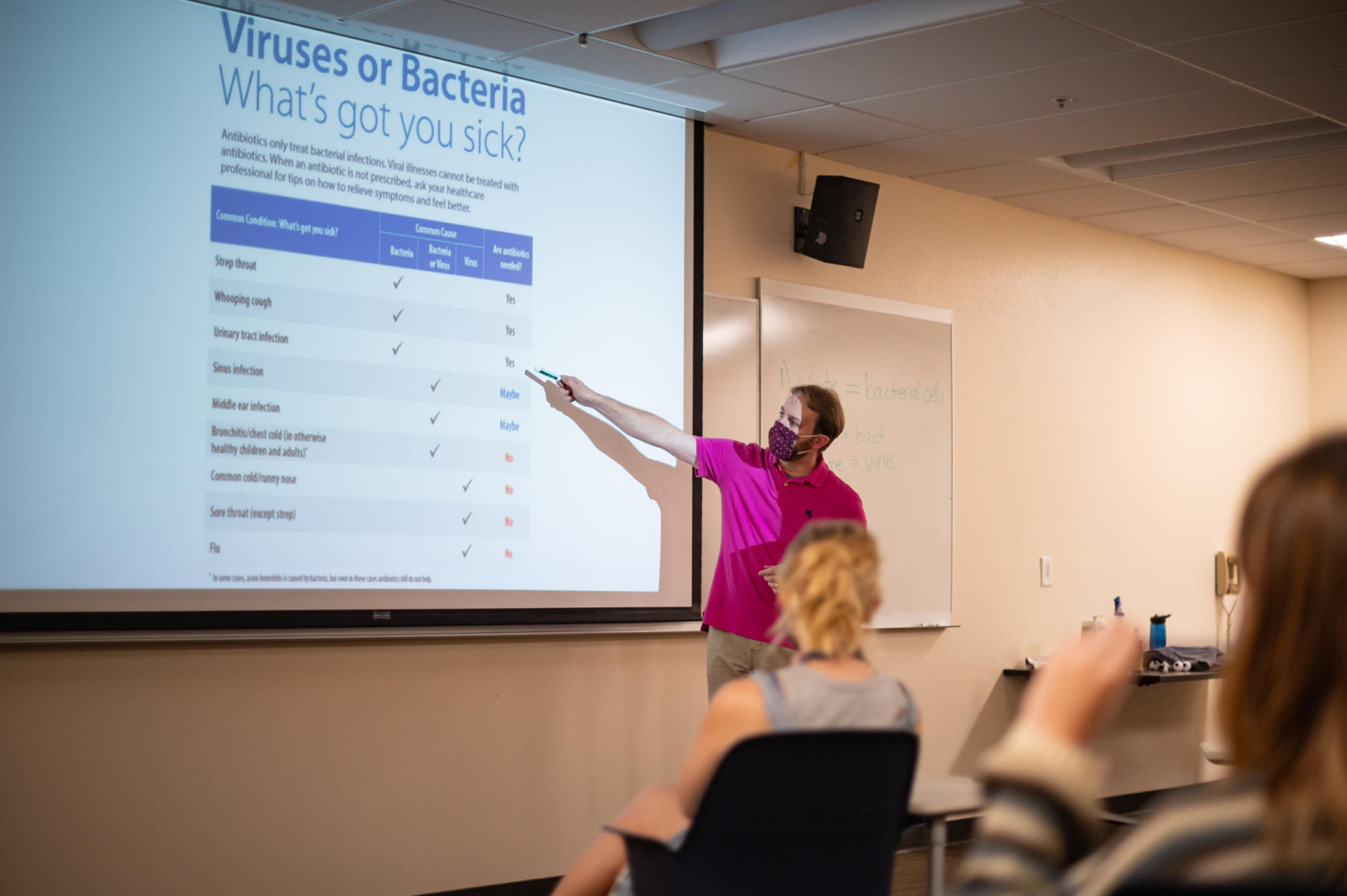

There can be a lot of pressure, Cline, explains, to take antibiotics “just as a precaution.” But that’s not always best. He and the students then delve into a discussion about the many incidences where antibiotics are errantly prescribed and the bacterial resistance that can result.

For his last exercise, the white and orange balls denote good and bad bacteria. As the claw (the antibiotics) attacks them indiscriminately, the students nod while he explains how antibiotics often kill off more good bacteria than bad.

“It’s so interesting to learn more about medicine and how it works,” said senior Andrea Torres Perez, who is an Asian studies major also minoring in biological sciences. She notes that the course has her reflecting on getting antibiotics as a child, consuming probiotics, and the recent COVID-19 vaccine.

Still in its infancy, the course’s small class size has allowed for robust discussions. Cline said he has found the students’ base understanding of biology allows him to dive deeper than he anticipated. Last semester, a reading on the ethics related to CRISPR gene-editing technology and controversy over its use in China made for a vigorous conversation. They’ll soon spend several weeks talking about vaccines and the efficacy of masking.

“I feel like I’m creating a class environment where expressing an opinion that goes against the group consensus is welcome, so we can look at the data and discuss how we reach conclusions,” Cline said. “There is a lot of inherent interest in the topics that the students are anxious to discuss.”