Serving the Spectrum

Jennifer Pickering had secured her son Grayson into his rear-facing car seat hundreds of times—at this point, the routine was rote. But in this instance, gazing into his blue-green eyes as she clicked him in, her life felt exponentially different.

Moments earlier, Grayson had been diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Not yet two years old, smiling, sandy-haired Grayson already had a lifetime of health and developmental challenges. Weighing just three pounds at birth, he spent the first 18 days of his life in the neonatal intensive care unit at UC Davis Medical Center. Over the ensuing months, Grayson began presenting developmental concerns. He has vision issues in both eyes, and his feet developed without arches and frequently disconnect from their joints. He was slow to meet certain milestones, and he wasn’t verbal.

With the ASD diagnosis, Pickering’s vision of a healthy childhood for Grayson had gone murky. What kind of services would be available? Would he have what he needed to thrive? And how could she ensure her son lived the life he so richly deserved?

“I felt it in my heart, in my chest. It was this feeling where it’s something you can’t control and you want to say, ‘No, no, it’s not that, he’s fine,’” Pickering recalled. “But I also wasn’t going to deny him the help he needed just so I can believe he doesn’t have it.”

Her quest to support their new reality led her to Chico State’s Autism Clinic.

Since 2003, the University’s Autism Clinic has supported the sensory, motor, communicative, and cognitive skills of people with autism through a multisensory approach. Designed as a service-learning program, it annually provides about 70 families with fitness and nutrition activities, social programs, and individualized assessment and goal-setting for children ages 3 to 18.

“We are helping families in ways that they never expected or might not have imagined possible,” said clinic director Josie Blagrave (Kinesiology, ’04; MA, Kinesiology, ’07). “Through these services, we are supporting and empowering individuals on the spectrum and their families to live their best lives.”

In the last two decades, national research shows autism diagnoses are rising exponentially. Using data compiled by its Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, the Centers for Disease Control reports that in 2000, 1 in every 150 children was diagnosed with autism. By 2016, rates were 1 in every 54 children. And with no scientific explanation, boys are 4 1/2 times more likely to be on the spectrum.

Individuals with autism perceive and react to the world around them differently—and face a number of challenges as a result. Difficulties with personal interaction can lead to missing social cues and communicating differently than their neurotypical peers. Their behavior patterns can be restrictive, repetitive, or both—ranging from overwhelming interest in something new to an adamant adherence to routines.

Adding another layer of complexity is a vast range of co-occurring conditions, including hypersensitivity to sounds or light, gastrointestinal issues, anxiety, and difficulties with concentration, tantrums, and self-injurious behavior.

Blagrave and others are constantly working to dispel misconceptions about the disorder, whether that it accompanies an intellectual disability or that it means the children can’t have an emotional connection.

“A lot of therapists told the parents when their kids were diagnosed, ‘your kids are never going to love you, they just see you as a tool,’” she said. “It couldn’t be further from the truth.”

Another major misconception relates to their ability and interest in physical activity. When the Autism Clinic first opened, scientists looked at individuals on the spectrum—and how they responded to exercise and movement—differently. Motor skills and exercise were not evidence-based practices and simply not considered.

“We’ve always intuitively felt that what we were doing here was right, but it took the research 10 years to catch up,” Blagrave said.

Research now reveals that autistic adults love physical movement. But because many weren’t given that opportunity to work on motor skills as children, they’re just not good at it as adults—and they wish they were. So, the Autism Clinic has made early development of those skills central to its services. When a family brings its child to the clinic, Blagrave starts with a very specific question—often catching them off-guard.

“I ask them to tell me all the awesome things about their child,” she said. “A lot of times they tell me what the child can’t do, and I say, ‘No, tell me what they can do.’”

The approach forces parents to consider the child’s strengths, rather than their weaknesses—which is often how society (and many medical professionals) perceives children on the spectrum.

“It’s so sad and interesting to watch parents say, ‘Hmmm, what does my kid do well?’” Blagrave said. “I’ve had parents just be totally flustered over that question, because no one has ever asked them that.”

Ultimately, it’s OK, because at the clinic they will discover the answer together.

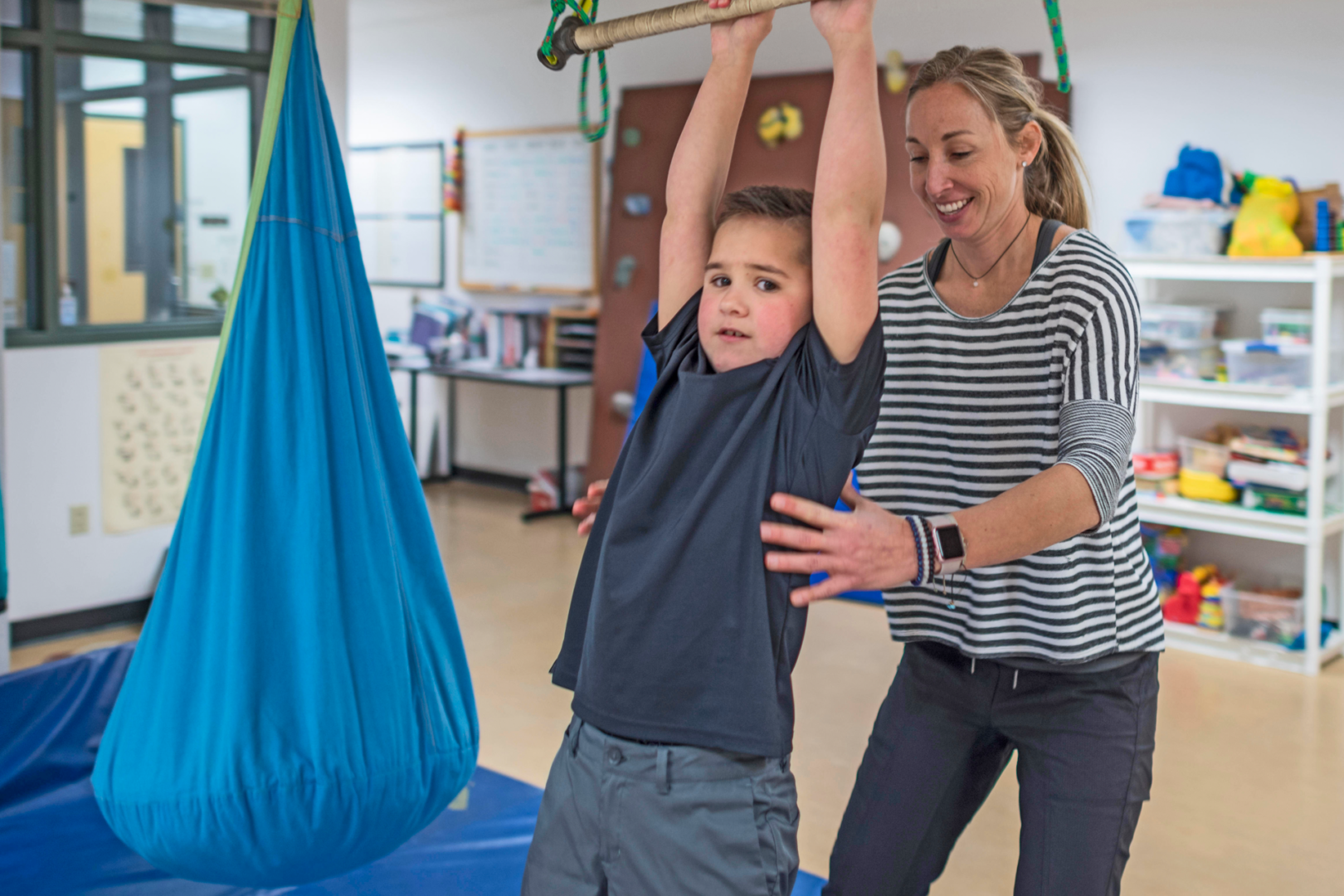

Located in Yolo Hall, the clinic offers a simple, tidy space with lots of room to move freely. The sports equipment ranges from buckets of balls and stacks of Frisbees to Hula-Hoops and basketball hoops, balance balls, and a foam pit—all designed to help the children gain a better understanding and eventual mastery of gross motor skills.

Each 50-minute session begins with a list of activities the clinician has outlined for the child for that day—from throwing and catching a ball to riding a bike outside—with the goal of working on skills you might see on a playground.

Cassy Comages has seen her eight-year-old son Mason work on these skills for more than five years at the clinic. He’s made remarkable improvements—and she credits the diligent and thoughtful care he receives in the one-on-one setting.

“Every kid is so different,” she said. “What’s so amazing is that the program builds each session specifically for the kid that they’re working with. And they just keep getting pushed and they have goals that they work on.”

Dozens of undergraduate and graduate students power the clinic’s services, with support from Blagrave and four clinicians. While largely kinesiology majors and those interested in a career in a behavioral field, like autism, students across disciplines are prepared for working with individuals on the spectrum in whatever profession they face.

“With no fewer than 20–25 students coming through every semester, multiply that by almost 20 years now that the clinic has been going, that’s a lot of students we’ve sent out into the world with a really great skill set they didn’t have before,” Blagrave said.

Katie Tiberi (Sociology, Psychology, ’19) interned at the Autism Clinic for two semesters. Now a licensed behavior therapist working in applied behavioral analysis in San Diego, her days are filled working with kids, teenagers, and young adults on the autism spectrum.

“The Autism Clinic gave me knowledge and experience working with the condition, and also allowed me to feel so comfortable in it that I couldn’t imagine working with any other population,” Tiberi said.

One of the most rewarding elements of her profession is when a child on the spectrum hits any kind of milestone, no matter how big or small it may seem to their neurotypical peers.

“We often take seemingly simple, everyday tasks for granted,” Tiberi said. “The feeling of being part of these ‘small’ victories for the kids and their families is something you could never fully grasp from a lecture or textbook.”

Small victories can mean the world to any child, but particularly those on the autism spectrum. They can be stepping stones for larger wins down the road, they can lead to significant breakthroughs, and they can boost overall confidence—like on a school playground which, for some children with autism, can resemble a battleground.

Whether they’re challenged by time-honored recess activities like throwing and catching or they’re just quiet and socially withdrawn, they can be singled out as being different—negatively impacting their self-esteem and opportunity for growth. The consequences get worse as children age, with statistics showing that people on the autism spectrum are seven times more likely than any other disability group to attempt suicide or have suicide ideation, and females on the spectrum are around eight times more likely than their neurotypical peers to be sexually assaulted.

“You see how vulnerable those with autism can really be, and I think, ‘how is this something that we’re not addressing?’” Blagrave said.

Early on, the Autism Clinic decided to expand its services and added a Teen Group program for kids 11–18, which meets once a week for 90 minutes and teaches life skills like maintaining an active lifestyle and healthy eating.

More than a decade ago, the Autism Clinic received a national grant to fund a partnership with the University’s Department of Nutrition and Food Science. The partnership established a comprehensive food lab program, now an integral part of the clinic, where Chico State students teach children on the spectrum about healthy food choices and safe food preparation.

In a kitchen setting inside Tehama Hall, Chico State students introduce different food options like fruits and vegetables they might not be familiar with, while also providing instruction on how to make healthy and hearty snacks, like smoothies and English muffin pizzas. The teens then move to the kitchen to work on food prep and making the snacks—all while interacting with each other and practicing social skills.

After each lesson, the teens eat the snacks they made together, see what they like and don’t like, and talk about what they’d do differently. The result is an increased willingness to try new foods, fewer food-focused arguments at home, and a drive to help more in the kitchen.

On weeks they’re not in the food lab, the Teen Group focuses on peer relations. It concentrates on complex social skills, how to work out safely and with confidence in a gym setting, and playing cooperative games—with the all-important opportunity to hang out and interact with their peers.

Blagrave recalls working with two girls their summer before junior high school. The clinicians set up a simulated locker room so the girls could practice opening their locker and changing in and out of gym clothes.

“We wanted to take that anxiety out of the actual skill part of that so they were comfortable transferring it into a school setting,” she said.

Blagrave is very familiar with the struggles of teens on the spectrum. Eight years ago, she and her wife, Jaime Cochran, a lecturer in the Department of Construction Management, adopted five-year-old autistic twins, Fabrice and Andrew, who were mostly nonverbal and still in diapers. The new parents took turns in the ensuing week being uncertain this was the right fit for everyone, as they struggled to adjust to the boys’ physical and emotional challenges. One night at dinner, Blagrave was walking behind one of the boys, when all of a sudden something compelled him to flail with his fork—jabbing her squarely in the chin.

“It was totally an accident, and I said, ‘OK, here’s where we’re going to figure out if this is going to work or not,’” she said. “He looked at me, grabbed my face, and just started sobbing, he felt so bad. His brother started crying, and soon, everyone was crying. I said, ‘This is going to work out, look at all of this emotion!’”

Both boys went to the Autism Clinic and now, at age 13, are in Teen Group. Blagrave said Fabrice is a natural athlete and isn’t bashful to introduce himself, but he struggles with anxiety, especially in sports. Andrew takes his time getting to know people and is quite attuned to social cues, but experiences more motor problems.

“Being a teen is hard. Being a teen on the spectrum is even more challenging,” Blagrave said. “The tools children of all ages learn at the clinic help make everyday interactions just a little bit easier.”

Seeing how far her own kids have come gives Blagrave hope for the children served at the clinic every week—and empowers her as a parent to communicate to students, clinicians, and families the importance of having a support system. She said the relationship is so much tighter than just being “clinic families.”

“Clinic isn’t just the one hour a week the families come in. So many of us talk to the parents outside of class,” she said. “It’s such a big family here and even if parents don’t know each other, there’s a shared connection. If you’re a clinic family, everybody is looking out for each other and really trying to help get all the information so they can all be successful.”

The clinic encourages all families to attend the Northern California Autism Symposium, which is annually hosted by Regional & Continuing Education at Chico State. The symposium brings together the entire autistic community—educators, practitioners, families, and individuals on the spectrum—for two days of education, resources, and community.

More than 200 people attended the fourth annual symposium last year, which featured 23 speakers on topics ranging from financial planning for families with special needs children and ways to avoid burnout to employment for autistic adults and choosing a college.

“It’s so hard for families to travel to get evidence-based scientific information to provide better support for their children. The symposium gives families in the greater North State access to information that they would not typically have,” Blagrave said. “Also, we put a big emphasis on having autistic speakers, which is pretty progressive and ahead of the curve.”

Whether it’s in person or at a conference, the Autism Clinic’s goal is to provide support in a most unique, specialized way—and one that gets to the very heart of serving North State families and communities.

When the COVID-19 pandemic forced the University to replace all in-person instruction with online instruction, the kids and families of the Autism Clinic were suddenly unable to receive the kind of instruction and community they were used to. So, the clinicians evolved and rolled out individualized and family-centered remote connections.

Each clinician is providing video and phone support to parents, meeting with kids and families over Zoom or FaceTime, recording videos of themselves demonstrating activities, and offering resources to keep everyone engaged and moving toward their goals.

“Our kids and families really rely on structure to be successful,” Blagrave said. “We’re doing our best to support families with that, even if it’s just in a small way.”

Today, Grayson is a five-year-old whirling dervish—running, jumping, and bounding his way through the clinic. His nonstop giggles bounce off the walls while his equally energetic clinician, credential student Taylor Guy (Kinesiology, ’18), guides him through a list of physically challenging activities.

At one point, Grayson runs up a ramp and jumps into a foam pit, where he allows Taylor to toss a soft rubber ball to him that deliberately bonks him lightly in the head. He falls over laughing—as does everyone else.

“I’m so glad we get to keep having the Autism Clinic,” Pickering said. “Because without it, I think Grayson would be lost.”

In the year and a half Grayson has been at the Clinic, she has noticed life-changing improvements.

“He’s not afraid to do things, he used to be afraid to touch the swing, he wouldn’t even go on it at all,” she said. “Now, he goes on that, he rides a bike. Sometimes, he just runs. He does things that give him joy. He needs to have a life with joy—and this is one of the best places we’ve found it.”