Student Shatters Statistics about Former Foster Youth

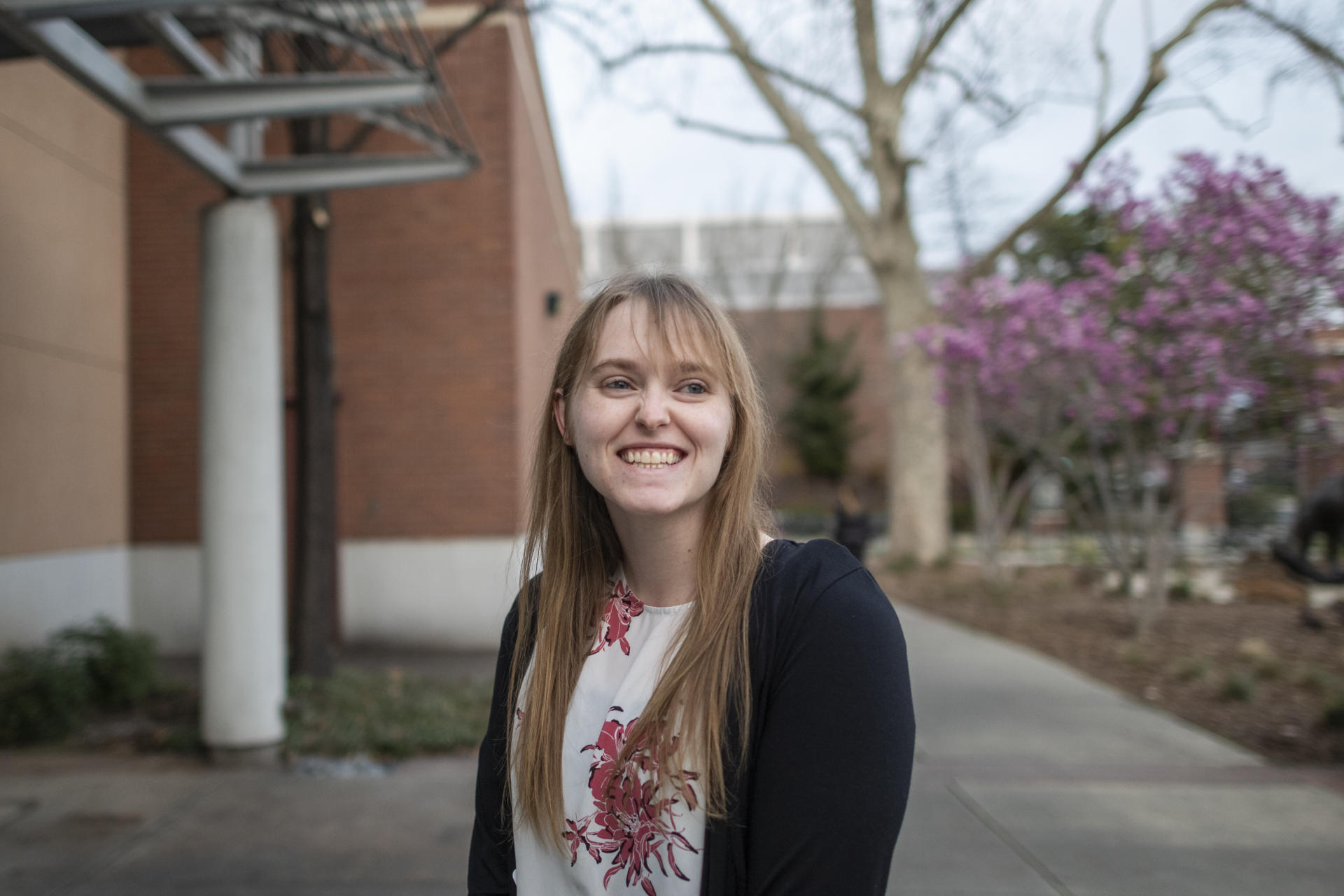

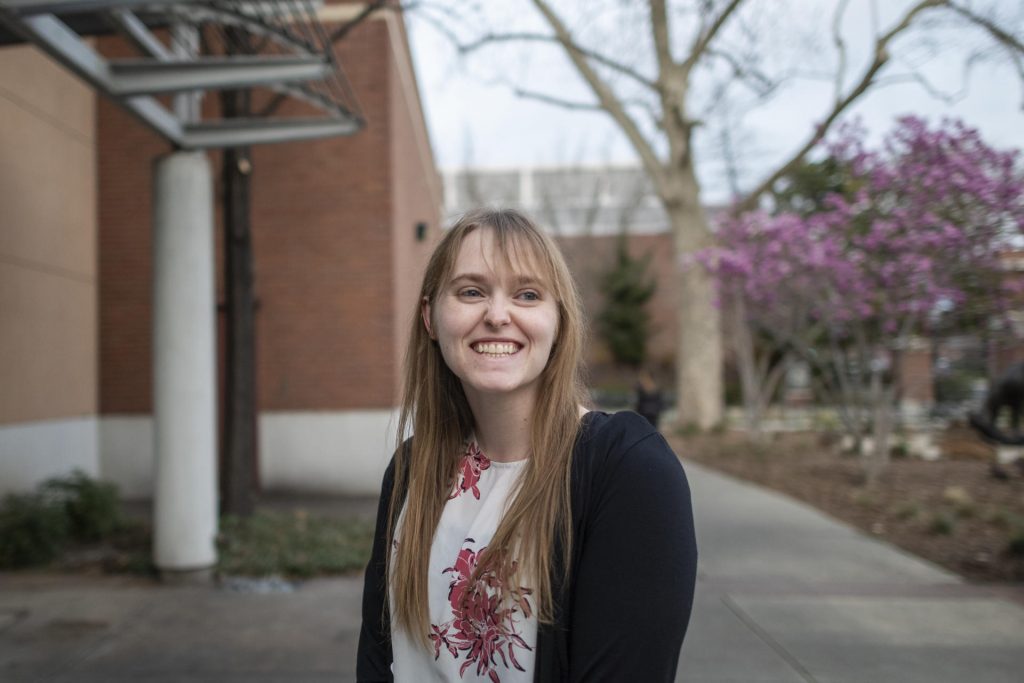

Caitlin Davis-Rivers recipient of the BSS Dare to Achieve Scholarship from the College of Behavioral and Social Sciences on Tuesday, February 19, 2019 in Chico, Calif. (Jason Halley/University Photographer/CSU Chico)

Caitlin Davis is fast asleep in her bed. Being a teenager, her life is already a roller-coaster of emotion, made only more tumultuous by the fact she’s entrenched in California’s foster care system. The family she’s living with is just one in a string of families she only recently met—and won’t really get to know.

A knock on the door jars her awake, and a slice of light from a hallway cuts into the room before the bedroom light is flicked on. Davis wakes up disoriented, but only for a moment. She instinctively knows what this means.

Child Protective Services is here to remove her from this foster home to live in another one.

It’s 12:41 a.m.

Davis is handed a few plastic garbage bags and given 10 minutes to gather her clothes, shoes, and any other belongings she doesn’t want to leave behind. Makeshift luggage in hand, the oft-repeated saying “You know you’re a foster kid when Glad and Hefty are designer bags” runs through her mind.

Davis doesn’t yet know where she’s going or how long she’ll be with the family that awaits her. Will this be the home she finally stays in, where she’ll feel like she belongs?

Less than 10 years later, the social work major would stand on the steps of the State Capitol in Sacramento and rally the crowd to support Assembly Bill 2247, designed to add stability to California’s foster care system. Its laws included a minimum number of days foster youth should be notified before they’re moved to another home, as well as limiting the hours when CPS can notify foster youth.

“That instability,” the Chico State student told the appreciative crowd on that sunny February day, “it hurt me the most out of all my years in care.”

AB2247 passed in September 2018. Davis takes pride in its passing, as she does for every victory she claims and odds she overcomes. When she earned the University’s inaugural Dare to Achieve Scholarship this year, it was as if it had been designed with her in mind.

More than 90 percent of California’s foster youth say they want to attend college, yet just 4 percent obtain a bachelor’s degree by the time they’re 26, as compared to 50 percent of non-foster youth in the same age group.

“Caitlin has had to navigate many systems and relationships, and she continues to persist. Her passion for social justice is demonstrated in her actions,” said Marina Lomeli-Fox, program coordinator for Promoting Achievement Through Hope (PATH) Scholars. “She goes to the Capitol and uses her voice to advocate for herself and her peers. She chose a career where she can continue to help and advocate for what is right in this world. She has joined that 4 percent and will work hard to keep increasing that number.”

Davis entered the foster care system twice, at age 4 and later at 11. She’s lived in 11 different homes. The longest stretch with one family is the seven years she’s spent with her current legal guardians, who adopted her.

The shortest stint was eight hours.

This was most of Davis’ life, hurriedly moving to live with family after foster family, existing within a system stretched thin by social workers who are overloaded and underpaid. And for any foster youth who yearn for a future after aging out of care—which she unapologetically describes as “broken”—Davis said the system falls woefully short in preparing them.

Now poised to graduate in May, she can’t help but marvel at how far she has come.

“In foster care, they don’t really tell you anything about school,” Davis said. “It’s like, the system doesn’t really care about your schooling as long as you just survive. … I didn’t know college was even a thing until high school.”

Davis dreamed of a career in social work. After graduating from Shasta High School (defying the statistic that only half of foster youth ever receive a high school diploma), she doggedly pursued higher education on her own.

At Shasta College, she sought out resources for students like her and joined the Shasta College Inspiring and Fostering Independence (SCI*FI) Foster Youth Program. SCI*FI counselor Bob De Paul became Davis’ mentor and right away noticed a remarkable inner drive lay beyond her quiet and shy nature.

“She seemed like she had a lot of dreams and ambition and was trying to figure out how to make those come true,” De Paul said.

After he took Davis and other former foster youth on a field trip to Chico State, she knew her next step. Davis transferred to Chico in fall 2016 and connected immediately with PATH Scholars, where Lomeli-Fox (Social Work, ’98) introduced Davis to the University’s available resources for former foster youth and unaccompanied homeless youth.

“I feel like it’s amazing once a student gets to Chico State that they made it here through all kinds of adversity from K–12,” said Lomeli-Fox. “It’s a process for them of starting to believe in themselves, advocate for themselves, and to say ‘Yes, I can do this.’”

In August 2017, Davis began interning at Children First Foster Family Agency in Red Bluff. And she continued volunteering for California Youth Connection, a foster advocacy organization she connected with while at Shasta College, and became the organization’s Butte County chapter chair at the end of 2017.

She’s no longer reluctant to talk about her turbulent journey like she was when she was in high school. The withdrawn teenager has matured into a young adult who speaks with the poised confidence of a burgeoning advocate.

Despite her continued work and advocacy, Davis wasn’t sure she would be able pay for tuition to finish her senior year at Chico State. She had applied for scholarships in the past, yet to no avail. But her lifelong experience with disappointment was no deterrent. With encouragement from Lomeli-Fox, she set her sights on the College of Behavioral and Social Sciences’ inaugural Dare to Achieve Scholarship, which considers financial need and work in the community on behalf of others.

When she learned she’d earned the scholarship, she was so relieved that would not be a setback in achieving her dreams. Add the fact that Children First offered Davis a full-time job in its Transitional Housing Program, the agency’s extended foster care side, after she graduates in May, and she finally feels like she’s home.

“I have a place where I know I belong,” she said.

Davis has come a long way from being yanked from home to home, and now envisions a future where she has a hand in helping to cushion the often-tempestuous world for California’s foster youth and to pave the way and show what’s possible.

“I have a job, and I get a pay raise once I get my degree,” she said, a satisfying smile washing over her face. “I’m doing well in life, and I’m hoping to inspire other people.”

It’s unsurprising that when children survive some sort of childhood trauma, they choose a career in which helping others is the focus, Lomeli-Fox said. And it’s no different for students who went through the foster care system, like Davis, when they choose social work as a career endeavor.

“I think a lot of students want to go back into that field and do things differently and treat the kids they work with more respect,” Lomeli-Fox said. “The way they wanted to be treated.”