The Digital Divide

Along the quiet roads to Rancho Tehama, the internet and cell service could be spotty, if not nonexistent.

Life in the Northern California town was not always easy for residents who loved its seclusion, affordability, and close-knit community, as they also longed for the technology afforded many of their urban peers.

Children could log on to the internet at school, but might live without service just a block away, making homework a hurdle and distance education a dream. It was difficult to entice dynamic new teachers, who wanted to work where they can make a difference but have modern conveniences in their classrooms and at home. For parents and other adult professionals, working remotely was little more than a wish.

Many knew high-speed internet could transform their town. But others worried it could change its intimate nature, be unsightly, and raise their cost of living.

That all changed in November 2017, when an emergency response to a shooting rampage was delayed due to poor cell reception and internet connectivity. Ultimately, five people were killed and 18 others injured at eight different crime scenes, including an elementary school.

In its grief, the town, population 1,400, became united to end its isolation. They embraced the changes that would come with better cell service and broadband—not just better public safety, but ending an exodus of younger generations to more urban areas by enticing them to stay and work in their hometowns. Widespread high-speed internet could give older generations easy access to much-needed specialist doctors through telemedicine. And of course, there would be opportunities for growing workforces and economies to thrive in new ways.

Improved telecom services came to Rancho Tehama in spring 2019. But it—like thousands of communities across the country—still struggles with the “digital divide.”

Amid the coronavirus pandemic, as much of the nation works and schools from home, the disparity between the haves and have-nots has revealed a telecommunications crevasse that perhaps no longer can be ignored.

Closing the gap has long been the goal of Chico State’s Geographical Information Center (GIC). For more than a decade, the center has been pioneering projects and supporting advocacy work that would improve broadband access across California. Its small but impassioned staff know that from the remote reaches of Tehama County to secluded pockets of Southern California, enhancing high-speed internet would advance emergency-services communication and public safety, distance education, healthcare, economic and workforce development, and quality of life.

“It’s kind of like the last frontier, like connecting that last mile of telephone line,” said Jason Schwenkler, executive director of the GIC and the University’s Center for Economic Development. “We need it. We need it now. And we need it bad.”

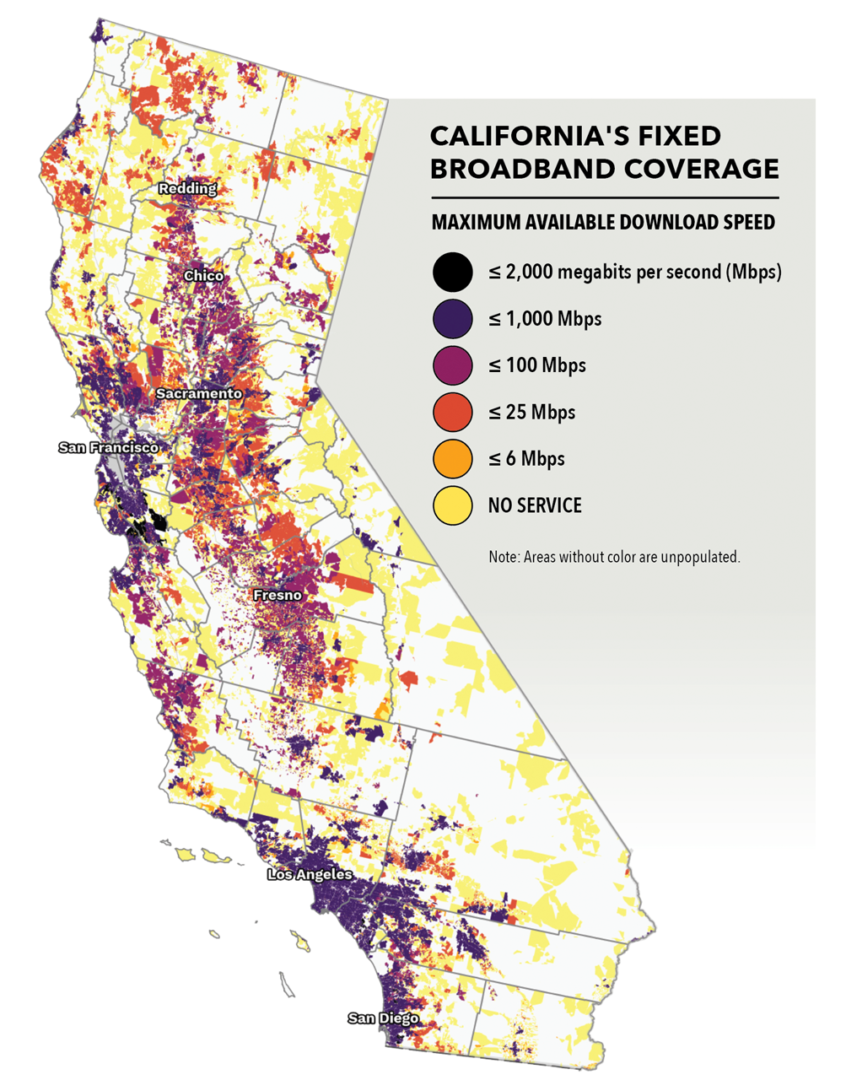

The GIC reports an estimated 7.5 million Californians don’t have or subscribe to broadband, and others are severely underconnected. The greatest disparities lie in rural communities, especially the mountainous regions of Northern California. The worst is in Alpine County, where 82 percent of residents lack such technology and access at current California standards, Modoc County (56 percent), and Sierra County (53 percent).

Even in population centers such as Los Angeles County (1 percent), San Diego County (3.3 percent), or Santa Clara County (2.5 percent), the margins may be small but they still reflect hundreds of thousands of disconnected individuals.

High-speed internet access is generically referred to as “broadband” and defined by governmental agencies in terms of data-transfer speed. The California Public Utilities Commission has set benchmark speeds of least 6 megabytes-per-second (Mbps) download and 1 Mbps upload. A video call requires at least 2 Mbps. Streaming movies takes more than 3 Mbps.

The GIC began working on broadband in 2007, recognizing that wide bandwidth data transmission was not just severely lacking in significant portions of the North State, but absent in some areas altogether.

“We started by just going out and talking, do people want this?” Schwenkler said.

The answer was a resounding yes. Yet, 13 years later, this divide still exists.

Infrastructure remains the biggest obstacle, as the installation of towers, fiber optics, and other technology to support high-speed connectivity requires a serious investment. In Northern California alone, the GIC aspires to bring broadband to a region the size of Ohio, crossing densely forested mountains, sprawling farms and rangeland, and desolate roadways. There is little enticement for telecommunications companies—which hold much of the power—to make such a significant investment when the number of connected subscribers would be so low.

“It really is like fighting Goliath in a lot of ways,” Schwenkler said.

Today, the GIC is the lead agency for the Northeastern and Upstate California Connect Consortia, coordinating funding opportunities, and deploying and expanding broadband infrastructure throughout rural Northern California and beyond.

Together, they hope to resolve the digital divide. This technology gap among socioeconomic or ethnic groups also represents the miles that separate those who are connected from those who are not.

Closing the divide, says California Governor Gavin Newsom, is critical to support the economy, equitable opportunity, and quality of life for all Californians. Last year, he announced an inclusive “Broadband for All” initiative, created in partnership with educational agencies, government entities, and the private sector.

The commitment has since assumed a new sense of urgency amid COVID-19. With no idea how long everyday activities may be restricted and the benefits of remote connections growing more obvious every day, projects finally could start catching up to demand.

“I’m glad everyone’s talking about it now,” Schwenkler said. “For me, it’s a passion that this has to happen for our economy, for our region.”

Perhaps no one is more excited by this small silver lining than David Espinoza.

Born and raised in Lima, Peru, after college he started deploying radios and communications systems in remote areas such as the Amazon rainforest and the Andes Mountains. Witness to the remarkable transformation on healthcare and education these communications systems brought, he wanted more.

But first, he needed a better understanding of the barriers to advancing such projects—funding, politics, economics, and policy. He enrolled in a master’s program in the United States, and then a doctoral program where, for his dissertation, he analyzed how new technology could be deployed in Peru.

However, he was starting to see regions of the United States had parallels to the communications challenges of his native country. After completing his PhD in telecommunications, he immediately accepted a job as a broadband specialist at Chico State and manager of the Northeastern and Upstate California Connect Consortia.

“At the time, I didn’t realize there were rural areas of California that were underserved, that people were still using dial-up, or areas with no internet at all,” he said.

Today, as Espinoza drives around the North State, stopping to take pictures of postcard-like scenery of sprawling farms outside Alturas and charming downtowns like Mount Shasta, he can’t help but imagine what high-speed internet could do for them.

“With broadband, you can turn a laptop into a classroom, a computer into a doctor’s office, a home office into a business,” Espinoza said.

He had found his calling.

In addition to deep dives into the latest broadband research and meeting with rural local governments, organizations across the North State, and statewide broadband stakeholders, a key part of Espinoza’s work is supporting specific community projects.

So far, six have been funded by the California Public Utilities Commission’s California Advanced Services Fund. That includes $21 million in Plumas, Lassen, and Modoc Counties to bring broadband to an estimated 636 households.

“Every one of those projects was challenged,” Schwenkler said. “But for once, leaders said ‘Those challenges do not have enough weight compared to what [broadband] could do for the citizens of our region.’ For us, it was a huge win.”

The GIC was also a supporter of Rancho Tehama’s new cell tower, which enhanced connectivity on multiple platforms, and also helped the local internet service provider test to pursue a grant for improved wireless.

Another major victory was a $50,000 Facebook grant. As the social media giant funded other projects by Cambridge University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Carnegie Mellon University, it also awarded Chico State funds for an economic and policy impact analysis about broadband availability and adoption across California. While small in dollars, the prestigious grant will support research on not only what areas are not served but what specific populations may be disproportionately suffering, whether by race, gender, age, or otherwise.

The center also had success on conducting a study to equip all 74 California fairgrounds with adequate broadband and telecommunications infrastructure to support local, regional, and state emergency and disaster response, along with potentially thousands of evacuees.

There are, Schwenkler said, perhaps no two better examples of this need than the 2018 Camp Fire and the 2017 failure of Oroville Dam’s auxiliary spillway. During both instances, the Silver Dollar Fairgrounds in Chico was inundated with emergency responders and evacuees all in desperate need of communicating, but the internet system was completely overwhelmed. Many other fairgrounds designated for emergency response by the California Office of Emergency Services lack the critical broadband capacity to handle thousands of users.

“One of the main reasons we are starting to have some momentum of success is we are tackling these problems with a multidisciplinary approach,” Espinoza said. “Each of these organizations speak a different language. Some speak policy, some technology, some local government. And we are helping them all work together.”

The GIC assists the state utilities commission in testing cellular service coverage and speeds at 900 locations across California (a partnership with CSU, Northridge), and also promotes citizens self-report broadband internet coverage and speeds using the CalSPEED application (a project led by CSU, Monterey Bay).

On a local government level, the GIC assisted with a fiber-optic network design for a pilot project in downtown Redding. Based on the study results, the city is now applying for funding to carry out this project, bringing readily available high-speed internet to more than 1,300 businesses and homes.

The center has also been supporting cities with adaptable telecoms plans that can be incorporated into their general plans and drafting “dig once” policies, where coordination for broadband installation is automatically included with undergrounding utilities when trenching occurs.

Paradise was one of the first communities to adopt such a policy. As they work to recover from the deadly and devastating Camp Fire, town officials know that offering the technology of a major urban area with all the beauty and close-knit community of a mountain town could spur vital economic development and investment.

Schwenkler hopes that public and private partnerships could create a baseline of gigabyte-per-second download speeds. Such technology has only been around for a few years and is only in a few cities, but it’s certainly the future—and there is no reason it can’t be in the North State.

“I want us to be able to say, ‘Gig service is coming! A gig city,’” Schwenkler said. “And I hope it’s Paradise. That would change everything.”

While working from home in recent weeks, Espinoza and Schwenkler said their phones have been ringing nonstop as people seek out the expertise they are so willing to share and initiate conversations about potential projects across the North State.

“I like that we are helping with the short-term solutions and that all those conversations are talking long-term,” Schwenkler said. “That’s the first time we’ve seen that. They are saying, ‘This is what we need now—and make sure we are in it for the long haul.’”

One area of renewed interest is related to telehealth, as the COVID-19 pandemic has forced physical and mental healthcare to be delivered virtually—but to do so, infrastructure must be in place, said Celeste Jones, a professor of social work and distributed learning coordinator.

“The rest of the world is seeing what many isolated communities have dealt with for a very long time,” Jones said. “It’s like, welcome to our world now.”

Broadband creates opportunity for telemedicine for gerontology, rheumatology, pediatrics, psychiatry, cardiology, pain management, and many other specialties that residents of rural communities simply don’t have local access to. She’s been working with the GIC in recent years to support the California Telehealth Network to identify why rural healthcare facilities and physicians have—or have not—adopted virtual systems. Her research shows that often it’s not the healthcare provider that lacks broadband, but their patients.

“It doesn’t matter if a doctor has broadband if their patients can’t connect,” Jones said.

Another challenge is some insurance companies don’t want to reimburse providers or policyholders if it’s not face-to-face contact. However, if they can realize the significant cost savings if people can be treated remotely instead of in person for minor ailments, or be referred to the specialist they need without an in-person visit, they could and should help drive this change, Jones said.

“What’s been absolutely fascinating is with this switch with COVID-19, that is the only way we can communicate. It has opened up a more comfortable level with [telehealth] and connecting with people,” she said. “It’s just shifted those that were apprehensive of doing it or felt that it couldn’t be done, now it’s the only way.”

Education professor Ann Schulte has long been advocating for residents of remote California. As a faculty fellow for the University’s Rural Partnerships, she knows firsthand that many already want broadband, and others simply need to learn more about its benefits.

“Our rural regions are not wastelands to be left,” she said. “They are something to invest in. We shouldn’t let those communities die and let those people recede.”

One of the greatest challenges is that children have access to the entire world at school, made possible by a statewide broadband program for educational institutions, but they may live just a block away with no internet at all. Which means their only way to access it after high school is to leave. Many never return.

“Sometimes rural teachers say they spend time helping the ‘good kids’ get out,” she said. “I think that is the wrong message to a rural region. They need people to stay and come back.”

They also need teachers who want to work in those communities, and other job opportunities. Everyone should see these rural towns as opportunities for a great quality of life. In today’s world, broadband is an integral part of that, Schulte said.

“In preparing teachers to work in rural areas, we teach them to work with students with a strong sense of place,” she said. “Where we are from shapes who we are. It’s about a sense of belonging and connection. We want to say to them, ‘Your place matters.’ We want to be a part of them having choices, rather than just staying and rejecting change, or leaving and never coming back.”

Schulte, Jones, Espinoza, and Schwenkler ultimately share a similar hope—that the COVID-19 pandemic will drive a long-awaited tidal shift in telecommunications technology that will transform lives well across the North State, California, and beyond.

“A lot of things have held us back. This forced it,” Schwenkler said. “Things are going to be different. We need to be more creative, more inventive. We need to recognize it as a true investment, as the next version of ourselves.”