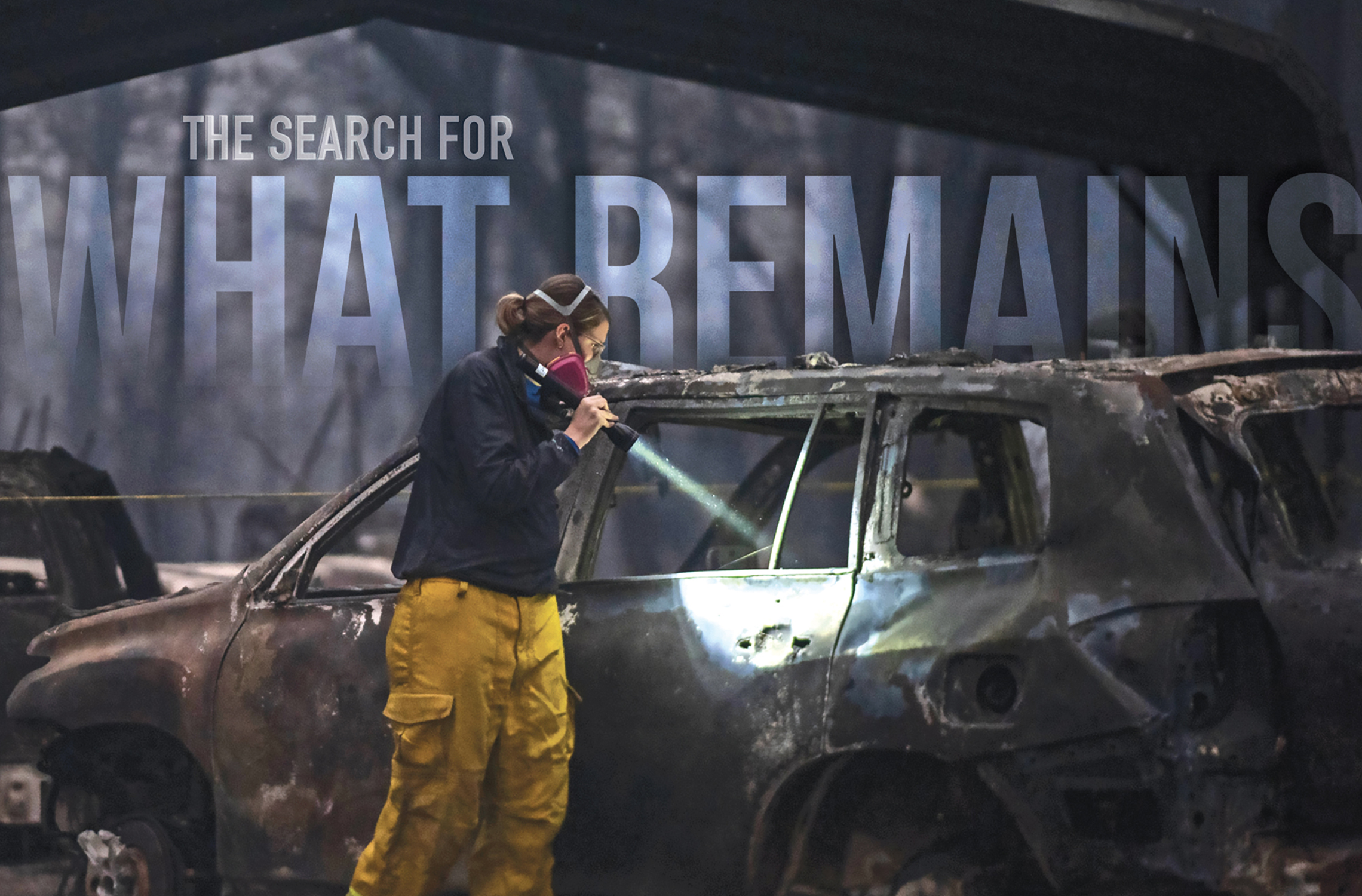

The Search for What Remains

By 6 a.m. November 10, less than 48 hours after the first flames started licking at the forest floor, the recovery team dispatched to the Camp Fire. Slowly navigating a charred and winding mountain road, the anthropologists made their way into the rural foothill communities.

The scene was otherworldly. Electrical wires lay melted across the roadway, a few still burning. Gas lines that had not expended their fuel were still firing off like torches. Smoke cloaked the once-dense forest like fog.

“It’s like Mars. Nothing is recognizable,” said Karen Gardner (MA, Anthropology, ’13). “A house is now 6 inches thick, with all that’s left of it. That’s the floor and the furniture and the walls—everything.”

One day earlier, professor Colleen Milligan’s cell phone rang. It was a call she was expecting.

The forensic anthropologist had been watching as a plume of smoke stretched from the foothills across the valley, cloaking the Chico State campus in darkness amid reports the inferno had already leveled Paradise and other communities in a ravenous push toward the valley floor.

Milligan, herself evacuated, confirmed to the Butte County Sheriff’s Office that the University’s Human Identification Laboratory (HIL) team was immediately available to assist with victim recovery.

It would be days before the team realized the magnitude of what lay before them and weeks before their exhausting work would be done. In all, Milligan and the HIL anthropologists would assist with the examination of 14,000 destroyed structures and thousands of vehicles in a burn scar stretching 239 square miles. As the Camp Fire’s infamous death toll reached 85, they helped recover the remains of its victims, 11 of whom are still officially unidentified six months later.

“When it is your home community, you want to know that the best resources possible are being used,” Milligan said. “We know what our lab is capable of, we know what we are good at, we know what contexts we are most useful in. There is not another lab like ours.”

For nearly 50 years, the Department of Anthropology’s HIL has offered experiential learning for Chico State undergraduate and graduate students while providing forensic anthropology consultations and related services for local, state, and federal agencies.

In addition to lab analysis of human remains and law enforcement training, the HIL’s unique expertise includes search and recovery fieldwork of outdoor scenes, including sites of major disasters such as wildfires.

Operating the most experienced forensic lab west of Texas, the HIL’s faculty members represent half of the board-certified forensic anthropologists in California. The team is available at all hours year-round, regardless of whether the University is in session. (Read more about the HIL)

Truthfully, few other universities in the country would have been able to compile such a team for the Camp Fire, either in magnitude or in terms of fire experience, explained HIL Supervisor Alex Perrone.

“We are the team,” she said.

For the Camp Fire, they were asked to locate and confirm the findings of human remains, which were then sent to the Sacramento County Coroner’s Office for identification. In all, 39 faculty, staff, graduate students, undergraduate students, and alumni would represent the HIL in the search—many of whom dropped everything to respond.

“The opportunity to be able to do something that is so vital and urgent and important is an incredible privilege,” said Gardner, who returned as an alumna to support the HIL’s work. “The skeleton is the most personal thing we leave behind when we are gone. … It’s about finding them and giving a family closure, telling the stories of people who can’t tell these stories themselves.”

Searching the rubble of the first house took about an hour, finding nothing, and the team moved to the next one.

The HIL anthropologists initially searched for known fatalities, the ones first responders encountered as they conducted evacuations and scoured the fire’s path for survivors. They moved next to areas with a high likelihood of deaths, addresses where 9-1-1 calls were made or loved ones had told law enforcement about vulnerable residents with mobility or health issues.

With about 10 searchers per home, the anthropology team moved methodically in a row across each structure, using hands, shovels, and trowels in search of anything that looked skeletal. Beds, bathrooms, and doorways—known places of refuge during a fire—were given special attention.

Despite a common misconception that cremated remains are reduced to dust, most bones remain identifiable, though they may be highly fragmented and fragile. For those who are trained in skeletal shapes—the rounded ends of long bones, long tubular rods, vertebrae—detecting remains is not as difficult as it may seem.

It may shatter, but ultimately, “bone still kind of looks like bone,” Gardner said.

If any of the searchers said “stop,” everyone paused until they could determine, first, if the finding was bone, and second, if it was human. The discovery of hunting trophies and pet remains, which the anthropologists did their best to set aside for owners, complicated the search. Remains were collected as fully and carefully as possible, placed into a body bag, and given to a coroner’s office team.

“You have one shot at this. You have one shot to recover things in the best condition as best you can,” said HIL faculty member Ashley Kendell (MA, Anthropology, ’10). “You want to return essentially everything to the family if possible, and in the most respectful way.”

Locating remains is the vital first step in confirming fatalities. Without remains, an individual’s death will go unrecorded, their fate lost to history.

Each set of remains meant the death of one more individual who had been someone’s child, parent, neighbor, or friend. The confirmation of their passing spared loved ones the horror of finding remains themselves and aimed to bring closure.

“You look at the good you are doing by being able to tackle this really hard work,” said Lisa Bright (MA, Anthropology, ’11), who spent several weekends assisting. “You think, ‘I helped bring names back to 85 individuals.’”

With the fire not fully contained until November 25, the HIL team was largely working in an active disaster area. Each scene had to be cleared for falling trees, residual heat, sharp building material, open septic tanks, and other dangers before the anthropologists could begin their search.

Logistics changed daily, requiring a lot of flexibility, and the media were relentless. Once the rains came—a relief for firefighters—the ash turned into slippery, thick paste that only further encumbered their searches.

The scope of the destruction and the totality of the rubble were almost overwhelming.

“When in the United States do you lose an entire city?” Milligan asked. “You lose parts of town, not entire towns. So the information on a missing persons list is incomplete—everyone is technically missing.”

With support from the National Guard, Cal Fire, and dozens of search and rescue teams from throughout the state, the Camp Fire became the biggest deployment of human remains search teams in California history. And no national incident has had as many anthropologists on a day-to-day basis since 9/11.

In all, the HIL team spent 20 days in the field. They went through a year’s supply of gear in three days, depleting their University inventory of protective suits, respiratory masks, gloves, and other resources they use for recoveries.

There was no respite, physically or visually, from the devastation. Whether vegetation, cars and debris stranded in the road, or building rubble, everything took on a monochromatic palette of grey, black, and brown. The recovery teams became accustomed to the relentless sight of burned homes and trees and the slow return of animals to the area.

“At the end, you would start to hear birds or wildlife and you’d realize how long it had been since you had seen anything living,” Kendell said.

Every year, the HIL anthropologists assist on upwards of 20 field recoveries. Even on major fires, they typically leave in the evenings or every few days to trade shifts with fellow team members.

“Here, you never leave the disaster zone,” Perrone said. “Even at home, it’s raining ash.”

Every night, after the team had shed their contaminated clothes, showered, and eaten, they would huddle in someone’s living room to watch the nightly news report on fire conditions, the growing acreage, the number of missing individuals, and the inevitable updated fatality count.

“After the first four or five days, I was thinking, ‘I’m retired, do I want to do this?’” said Professor Emeritus and former HIL Director P. Willey. “I took one day off and realized, ‘There is no place I would rather be.’”

This awareness, he said, was as much about the need for the work to be done and the nature of what it required as what it was like to be in the company of his closest colleagues, serving a community he has been part of for 30 years.

“It was a wonderful feeling to be surrounded by so many current Chico students, graduates, and professors,” Bright agreed.

“You could trust every person who was there, the calls they would make, and the skills in their background. It was so great to know we have such a level of training and experience above and beyond other departments.”

The team was gratified by the respect and admiration given toward their professional field in a way none had ever really experienced before. As the search wore on, the impact of their skillset was continually recognized and valued.

“We’d get calls on the radio, ‘We need an anthropologist,’” Willey said. “And not just ‘want’—‘should have’ and ‘need.’ It was nice to hear that. Over and over again.”

Because so few law enforcement and other volunteers had searched for human remains in such devastating conditions, it was critical to provide training. Using donated cremains from the HIL collection and the skills faculty and alumni use in their professions every day, they taught searchers what to look for and what they were seeing.

At one of Gardner’s first calls with search and rescue, the team showed its finding and explained, “It’s so perfect, I don’t know if it’s real.” It was a wire-framed Halloween skeleton, yet another stark reminder of the normalcy and lives upturned by the fire.

Another day, she was called out to respond to a search and rescue team that thought it had found human remains. It was just building materials, a common mistake because building materials look so much like bone.

Gardner again shared some tips, suggested a method for searching, and returned to the area she had been working. Ten minutes later, she was called back to the same site. The team found the remains it was looking for.

“It felt really good that I could convey information in a way that led to their success,” she said. “There is no way to learn this other than to live it.”

Students took on the role of teacher as often as their faculty and alumni.

“You get a lot of questions, ‘Is this bone? Is this bone?’” third-year graduate student Karin Wells said. “We had to answer their questions without making them feel bad, be sensitive, and teach what we know in a way people can take that knowledge wherever they go next.”

The program’s first-year graduate students now have more experience than many professionals in the field, said faculty member Eric Bartelink (MA, Anthropology, ’01). The Camp Fire was also a continued lesson for undergraduates and master’s candidates in how to interact with law enforcement, conduct themselves in a professional and sensitive manner, and refine their recovery skills.

“You can’t get anything better in terms of real-life, hands-on anthropology experience,” said Wells. “There is nothing that can really compare.”

As anthropologists, the recovery team distances themselves from the emotional side of their profession in many ways, separating the innately human response to death from the scientific nature of their discipline.

“You have to have the right personality structure to either compartmentalize or work through the things we see in our everyday lives,” Bright said.

“We tell people who want to get into [the forensic field], ‘It’s not for everybody,’” she continued. “You have to look at the good things you can do for this work, because if you focus only on the sadness or the loss or the emotional devastation, you would not be able to get through the process.”

For many students, it was their first mass fatality.

“That first day, it was so hard. I just kept thinking, ‘This is a horror movie,’” said Leah Tray, a second-year graduate student who spent six straight days on the fire and returned a few weeks later.

Shattered china collections, the heads of dolls, coins fused in the shape of a piggy bank were constant reminders of the lives once within the walls of the homes they were searching. Setting aside that emotion doesn’t come easily, at least at the beginning.

“Every day got better. I proved to myself I can do it,” Tray said. “I’d rather get through it and find someone than have their families come back and find them themselves.”

The alumni and faculty were supportive of the students, as they always are, Wells said. As she prepares to graduate and pursue forensic anthropology as a career, she hopes she can further the culture of self-care and compassion among those who do this kind of work.

“Everyone has a different threshold of what they can and can’t do,” Wells said. “If they can only do it for three days and can’t do it anymore, that is OK. You have to take care of yourself because you can’t be helpful if you are falling apart.”

When Gardner was a student at Chico State, she lived in a cute alpine cabin in Magalia, with a loft and wraparound deck. She found respite from her graduate coursework in the tranquility of the pine trees, the ever-present wildlife, and the sound of the wind.

She had been assisting on Camp Fire recoveries for about a week when she found herself in the area and was able to drive through her old neighborhood to satisfy her curiosity.

At first glance, she second-guessed herself because the cabin’s familiar footprint was unrecognizable amid the ash and warped hunks of metal. But then she recognized the trees still standing out front.

“It was all very real before that, but that definitely brought it home,” she said. “It was close. I was there. That could have been me.”

SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

The Human Identification Laboratory works on more than 100 cases and recoveries each year. Your generosity can help the HIL expand its caseload and better serve local, state, and federal agencies with an upgraded facility and critical supplies.