Unearthing California’s Prehistoric Past

It was the find of a lifetime.

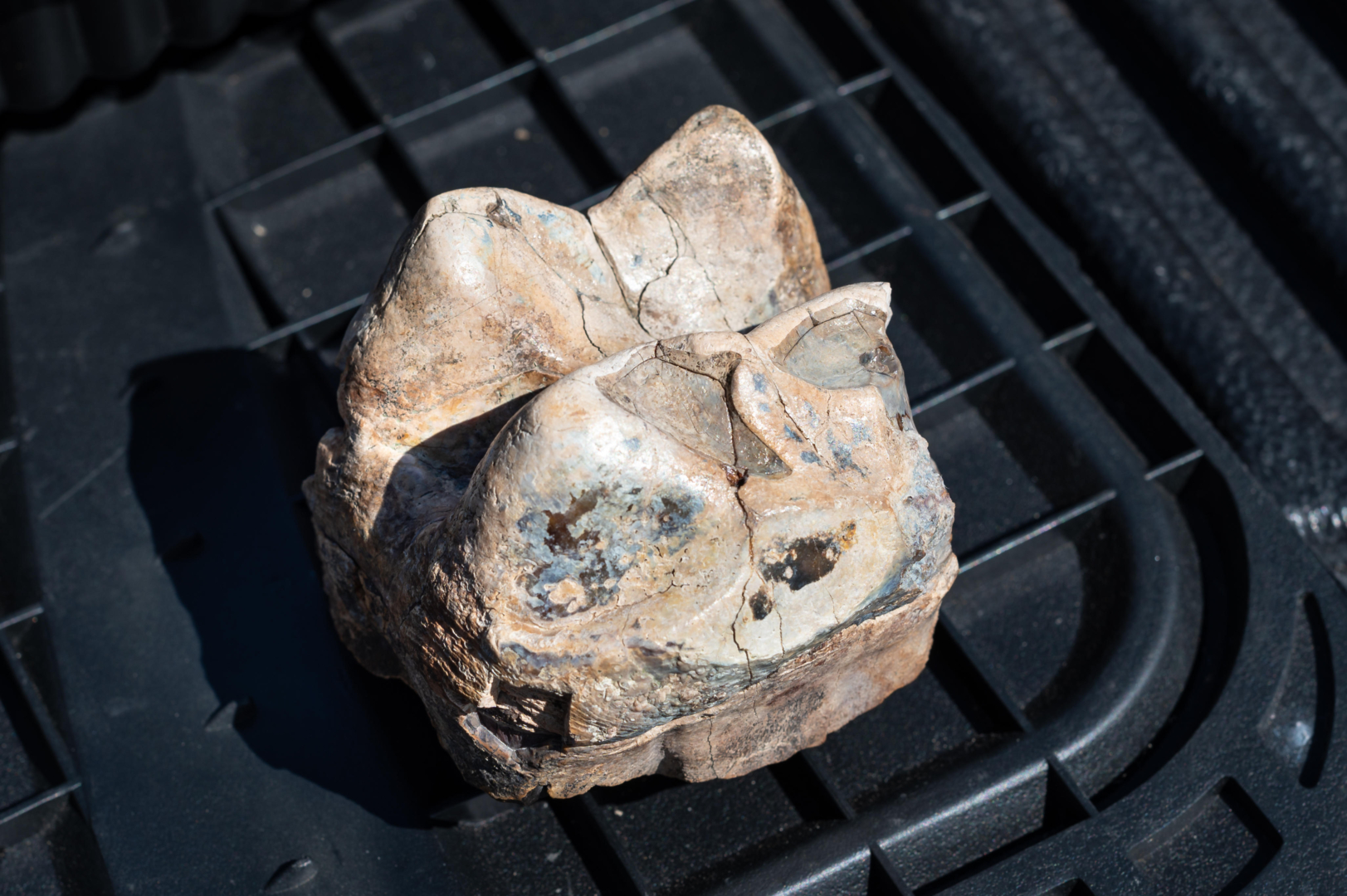

A softball-sized molar peeked out from the soft dirt, barely distinguishable except for a pearlized edge. As Russell Shapiro and the team gently began to pick away at the surrounding soil, a skull started to emerge, with more teeth jutting up from the jaw’s craggy border.

Then, a gently curving tusk started teasing its way toward the sunlight.

Ever-so-carefully, they pushed forward, hoping it would be intact. By the time they reached the end of the fossilized bone, all indicators pointed to not one but two six-foot spans. Perfect mastodon tusks. Likely dating back 8 million years. And the first known species of its kind to be discovered in this part of Northern California.

“What you hope to find is a tip of a tusk,” said Shapiro, a professor of paleontology and stratigraphy in the Geological and Environmental Sciences Department. “Not only do we have the tip, but we have the entire thing. And it’s just beautiful ivory. It’s mind-blowing.”

In the months that followed, so would more phenomenal finds. Shapiro, department chair and sedimentology professor Todd Greene, several staff members, and a handful of students continue to make regular treks to the site, never failing to discover at least one fossil.

Chico State is not revealing the site location—which is on 28,000 acres of protected watershed nestled near the base of the Sierra Nevada foothills—to safeguard its security while excavation work continues. The area is owned and managed by East Bay Municipal Utility District (EBMUD) on behalf of 1.4 million people in the Bay Area.

It was EBMUD patrol ranger and naturalist Greg Francek who first stumbled upon the fossils, quite literally. In summer 2020, he was on patrol in the watershed when he spotted something strange in the soil.

He crouched down and ran his fingers along its smooth surface. It looked like wood but felt like stone. Could it be petrified, he wondered? Then he spotted another piece. And another. His curiosity kept drawing him back and within three weeks, he had found what appeared to be vertebrate fossils.

EBMUD reached out to an environmental consulting firm, which immediately called Shapiro. The firm and similar companies have worked with Shapiro for years, turning to him for finds including a 15-million-year-old whale calf found in Southern California and a 25-foot-long ichthyosaurus near Lake Shasta. With students by his side, he leads the excavations and often guides processing and storage.

Shapiro, who received the Distinguished Career Award from the Geobiology Division of the Geological Society of America in 2019, researched museum records and learned only a single horse tooth had been found near the Sierra foothills site over the years. Not optimistic, he readied himself for a lot of searching and disappointment. His visit days later was a revelation.

Within weeks, Francek and the Chico State team had discovered the head of an elephant-like mastodon, a rhino skeleton, and more than 600 fossilized trees. And from the looks of it, there is much, much more. EBMUD, stunned by the discovery, funded Shapiro to hire assistants to do the collecting, and he reached out to alumnus Dick Hilton (MS, Geology, ’75), to see if he would lend a hand.

The first geology student to complete Chico State’s graduate program decades ago, Hilton is nationally known as the authority on dinosaurs in California and for his overall expertise in field vertebrate paleontology. Now retired after a 40-year teaching career at Sierra College, he eagerly accepted the invitation.

While he’s carried out paleontological digs from Montana to Wyoming, as well as led natural history trips to parts of Africa and South America, the Galapagos Islands, Baja California, and Alaska, this project, Hilton said, is an adventure all its own.

“It’s my favorite thing to do,” he said. “I just like to find fossils. It’s the little kid in me.”

In the last few months, Francek and the Chico State team have found two medium-sized mastodons, a giant tortoise, and four tusks from gomphotheres, which were elephant-like proboscideans dating to the Miocene epoch, which extended from 23 million to 5.3 million years ago.

The fossil site now spans 10.8 miles and hundreds of acres. On every visit, they tread softly, watching each step as they traverse the landscape in search of new discoveries.

“There! Is that part of a mastodon tooth?” Shapiro asked, laying down, peering through his magnifying glass to look for the telltale honeycomb pattern and overall density, and licking the specimen. A quick tongue test, as unconventional as it may sound, is one way to detect a fossilized object, as it should stick to your tongue. This one did not.

From 10 feet away, Hilton speaks up, “This might be part of a jaw.”

He pulls out a pocket knife and begins to scrape away at the soil. No, he determines, it’s more likely a rib. Francek takes a GPS reading, pockets the bone, scrawls RB for “random bone” in his notebook and they move on.

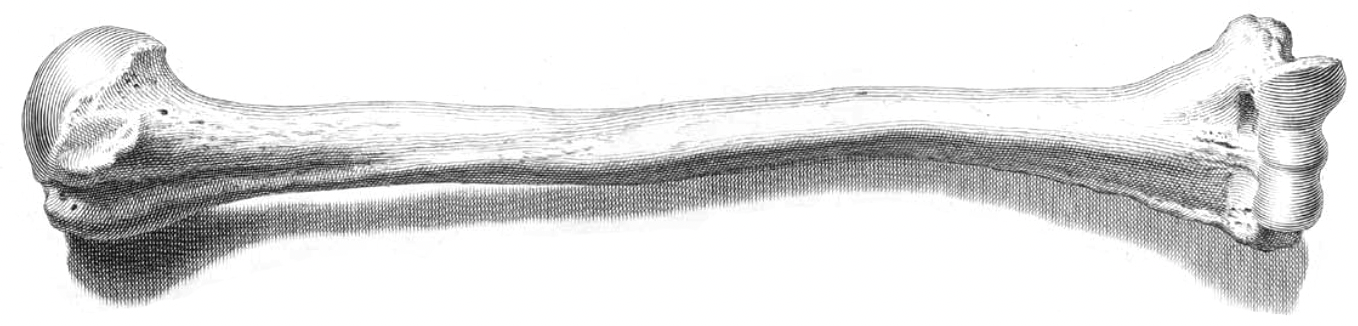

It goes like that for hours, as they gather every shard and every piece of bone they find, knowing that together they stitch a story of the state’s evolution. Eventually, they add a carnivore maxilla, two horse teeth, and a 3-foot-long humerus to the day’s findings.

Other exciting discoveries have included foot bones from a aepycamelus, a giant camel the size of a giraffe that would have browsed 20 feet up in the trees. The taupe-gray cannon bone is about 24 inches long and comes from the near the ankle, if that gives an indication of its gargantuan size.

They also discovered a tapir, a pig-like mammal with long snout that typically would be found in the tropical areas of Central and South America. It appears like it was young—perhaps still nursing—based off the lack of wear on its teeth and an unerupted molar, and might even be a dwarf species.

As the drought continues to impact the watershed, new fossils reveal themselves on every visit, Francek said. A former merchant marine captain, he’s taken a dozen earth science units and gone on several scientific expeditions, including recovering human remains in the Yucatan dating back 12,800 years—the oldest and most complete human skeleton ever found in North America. But little can compare to this, he said.

“It’s a university-level class with these guys every day,” he said. “The things that don’t make sense to me, I’ll show them to Dick and he’ll know right away.”

Their finds are slowly making their way to Chico State—one of only a few universities in Northern California that is federally sanctioned to collect and store fossils—where they will be prepared and ultimately sent to the University of California Museum of Paleontology. Chico State’s own collection, now housed in the new Science Building, includes thousands of specimens owned by the US Forest Service, US Fish and Wildlife, and the Army Corps of Engineers, among others.

“We have more projects than we know what to do with,” Shapiro said. “There are lots of opportunities for new students.”

Fossil by fossil, discoveries like this help unravel the region’s geologic history, the team agrees. And what a tale it is.

“These are some of the biggest finds since Merriam,” Hilton said, with a nod to the paleontologist John C. Merriam, known for categorizing the vertebrates at the La Brea Tar Pits and the taxonomy of the saber tooth cat. “This is fantastic. I’ve never seen anything like this in California. It’s simply prolific.”

The geologists hypothesize that this substantial collection is the result of floods and debris flows coming from volcanoes far to the east. Unlike the scenes we see in California today, the landscape was split into largely an ocean in its south and forest highlands in the north, “a state divided,” Hilton said. Giant mammals, like the ones found here, roamed the oak forests and floodplains while ancient whales and sharks lurked in the sea’s depths.

This discovery has added detailed complexity to the story we know to be true about California, long considered one of the most geologically diverse states.

“I can look out and picture a movie reel of the lands changing,” Shapiro said. “Through the trees, I see one group of elephants peek out as another walks by, and then great horses come in.”

“You think about what that all means. I’m really envisioning how this landscape is changing,” he added.

This transformation will be on display for the public to learn from later this year. The recently discovered mastodon skull and tusks are the centerpiece of an upcoming exhibit at the University’s Gateway Science Museum, along with the Miocene whale and ichthyosaur fossils from Lake Shasta.

But people don’t have to wait until the exhibit’s September 1 opening to see them. Every Friday and Saturday, visitors can view the scientists and students as they work to reveal and preserve the fossils in the museum’s lab.

“The exhibit will take you through time and how California has changed in animals, climate, tectonics,” Greene said. “And it’s fun because we get to show off a little bit.”

The long process of creating a museum-quality reveal is a delicate dance between preservation and revelation. The mastodon skull was found upside down, its two tusks crossed over one another. Shapiro and his team slowly dug around it before draping it with burlap sacks and plaster. Then, they undercut it fully below, flipped it over, and repeated the process to protect its journey north to the lab at Chico State, scrawling “mastodon” on the casing’s side with a permanent marker.

“We call them Easter eggs,” Shapiro said, a reference to the oversized white orb’s visual similarity. The name held true weeks later, when in early April, they cut the cast open to reveal the treasure inside.

The tusks span almost six feet in length and are nearly intact. The ivory, striated with shades of grays, yellows, and tans, looks pearlescent.

The tusks will remain partially encased in the dirt they were found in, which helps preserve them while giving context to the discovery itself. As the geologists scrape away the excess soil remnants, they drizzle the exposed bone with a mixture of acetone and liquid plastic, which helps stabilize and preserve it from damage.

Junior Erica Thompson, a geology major, said one thing she’s missed most during virtual learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic has been doing science firsthand. When Shapiro invited his students to take part in the fossil preservation, she leapt at the chance.

As she aspires toward a career in resource management and conservation, the chance to work on fossils from millennia ago has been nothing short of incredible, she said.

“It’s tedious, but it’s fun,” Thompson said, as she used a dental pick to nudge soil away from a horse rib bone recovered at the site. “We are unearthing something ancient and learning from it at the same time. It’s like hunting for treasure.”

Within hours of her first day in the lab, Thompson already felt she had a better grip on differentiating between bone and the surrounding matrix, as she let the texture, sound of the material, and a research textbook guide her movements. As she worked, she could not help but think about the various creatures comingling in real-life.

“It’s a nice way to let your imagination escape away from the realities of right now,” she said. “It’s like picking up a fantasy book and getting into a story someone has created. Even though you are not there, you are still connected to it.”

Instructional support technician Sean Nies (Geology, ’16) agrees. In addition to supervising the students, he helps lead the fossil preservation.

“This is what you think about when you were a kid,” he said. “It’s not often people get a call, ‘Do you want to go dig up a mastodon?’ I said, ‘Absolutely.’ And we stumbled upon this giant treasure trove.”

As a former art major, his success in a community college geology class led him to take invertebrate paleontology his first semester at Chico State. There, Nies blended his talents in drawing with an interest in science by penciling out prehistoric sketches, and he continues to find ways to combine those passions.

“I’m not making art, but there are a lot of techniques that are similar,” he said. “I’m not painting, but there is a certain level of art in prepping a fossil. It’s meditative. You kind of get lost in it.”

Armed with an array of paintbrushes of varying sizes and bristle stiffness, Nies gently sweeps away at the soil encasing the tusks, the gentle “whoosh whoosh” the only sound as he empties a small cavity. With a pick, he slowly reveals where the zygomatic arch would have been in the mastodon’s jaw, and a sinus cavity, uncovering a clam shell in the process.

“It’s kind of like the Jurassic Park stage. It’s very stereotypical removal techniques,” he said. “You want to preserve it in a way that’s visually appealing. Right now, it’s hard to tell what is bone and what is dirt.”

For Shapiro, this discipline is all about solving riddles—the more challenging, the better—and inspiring the next generation of scientists to continue the pursuit.

There are few colleges that offer these kinds of undergraduate research opportunities. He said he prioritizes including students on excavations because they demonstrate the practical use and career paths in ways students never otherwise would imagine.

Shapiro has been an incredible mentor, Nies said, especially with invitations to accompany him, whether at sites close to Chico State or a trip to France where the students were paid to examine the geochemistry of rocks.

“He’s given me a lot of opportunities and I tried to take every one,” Nies said.

That was Shapiro, decades ago. He wasn’t raised in a college-going family. But a fascination with topographic maps led him to a phonebook and a cold-call to an incredible mentor, who gave him research opportunities as a high school student that launched his future as a geology scholar.

“He once said to me, ‘The only thing you leave behind is your students,’” Shapiro said. “Now, I try to do as much mentoring as I can.”

He now dreams about teaching a class about the ancient life of California. Who knows, he said, maybe this new fossil collection could one day make that a reality, as he imagines painting tales for students of ichthyosaurus swimming around Redding and mastodons treading softly across the Sacramento Valley.

“It’s not just little kids who are into dinosaurs,” he said. “I think it would blow people’s minds, to say that you can find camels in Chico. And there’s a bit of pride in it too. If you love the area, think about what was here before.”

View a StoryMap of the discovery created by EBMUD.

Support the geological and environmental scientists of tomorrow by turning your gift into impact at www.csuchico.edu/transformtomorrow.