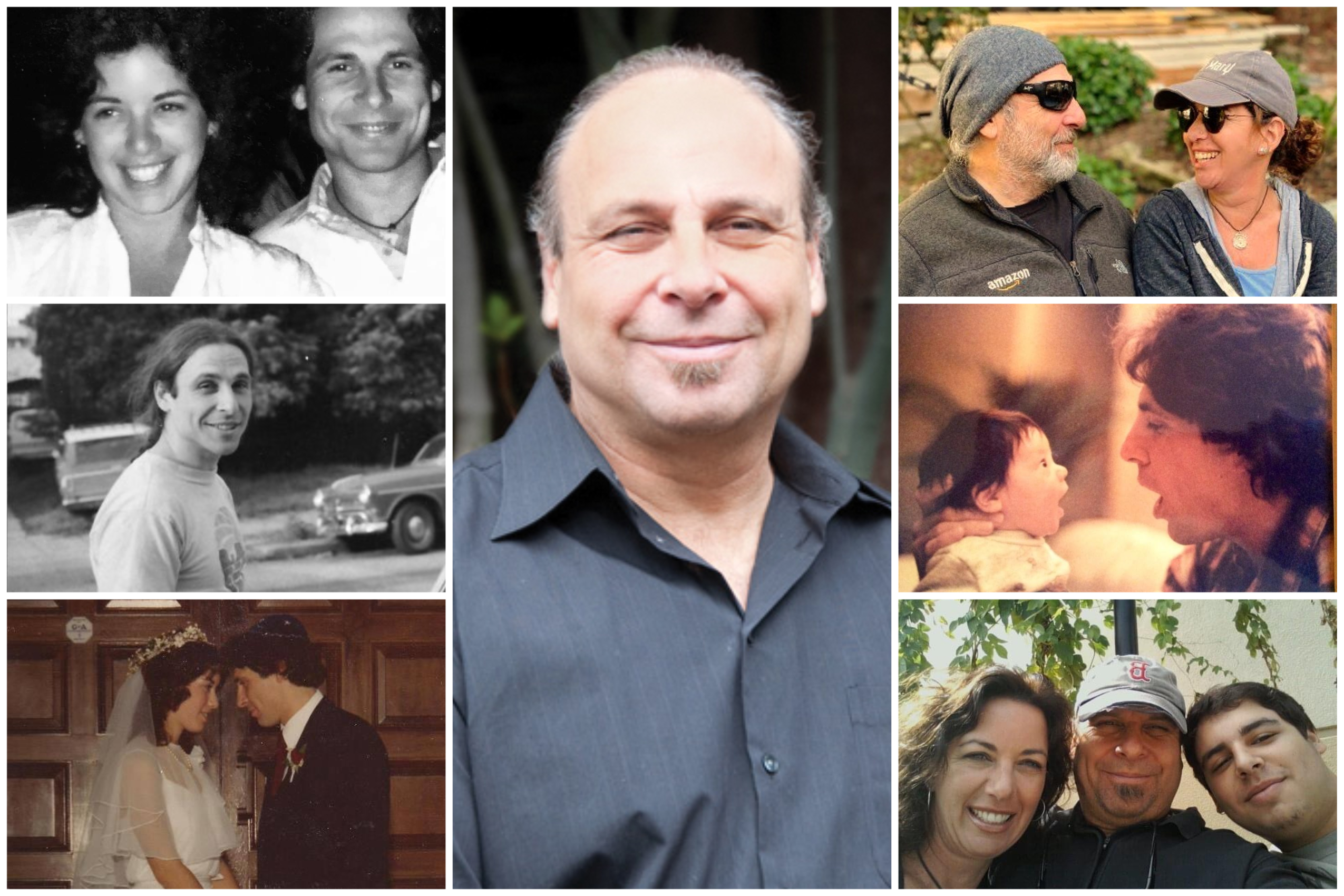

5 Questions with Alumnus Leon Warman

At 20 years old, Leon Warman (Mathematics, ’80; MS, Computer Science, ’84) had no idea his on-a-whim decision to attend college would lead him down a path of game-changing innovations that would shape the world as we now know it—he just didn’t want reach 40 and still be working as a machinist in the same run-down shop.

Coming to Chico State and choosing to study mathematics and computer science simply because he was “good at it” opened doors to unimaginable opportunities, Warman said. Those started with becoming a program engineer for NASA in 1982 and helping design the still-operating on-board flight software for the Hubble Space Telescope before its historic launch in 1990. NASA was only the beginning, as he went on to work for huge names in the booming tech industry, including Boeing, Philips, Entomo, and Microsoft before landing at Amazon, where he’s bounced around different departments for the last 12 years and now serves as senior principal engineer (or tech director) for Amazon Robotics.

Why did you choose Chico State?

I can tell you exactly the reason. I grew up in LA, and I was out of high school. I really never contemplated going to college. My parents were immigrants from Germany (both were survivors of the Holocaust), they were very blue collar. They didn’t really focus on [college] as much. They didn’t push me in that particular direction. I was working, making really good money being a machinist. But then, when I was 20, I looked around and said, “I don’t want to end up like these guys, 40 years old and working in a machine shop.” So, I was trying to figure out what I wanted to do when I and a friend took a road trip to visit our friend, who lived in Chico. I got there, and I was like, “Wow, this is really cool.” I really enjoyed everything about it. The atmosphere, it’s indescribable—everything jives. I thought maybe I could move up there, but what was I gonna do? There was no job, and by that time my parents [had] died. I could actually still collect death survivor benefits from the Social Security Office if I was a full-time college student (before the laws changed in 1981). I said, “Well, school is actually kind of easy for me, so I can take classes and figure it out from there.”

You were still a student when you started working for NASA on the Hubble Space Telescope. How did that opportunity come about?

I stayed [at Chico State] and worked on my master’s. At the same time, I met my wife. We were sitting around our living room in our little apartment, she’s five months pregnant, and it just sort of dawned on me that I ought to get a job. I looked at places [to live] where there’s some kind of job opportunity and a good school to do my PhD. I interviewed with different companies [during a job fair] and I just did a whole string of interviews for jobs in the Bay Area. One of them was to work on the flight code for the Hubble Space Telescope. It was interesting because there’s a very particular area of mathematics that’s used for guidance systems on space vehicles like that, or airplanes [etc.], and I just so happen to know it because [Professor] Tom McCready taught me all about this area of mathematics even though it’s not part of the curriculum, and it’s not really even used very much except in aerospace guidance application. They assumed I didn’t know [this type of mathematics], but I said, “I know all about it!” and I ended up getting the job. I worked on the Hubble for two years in the Bay Area. And I actually started my PhD at Stanford.

What do you consider your greatest career success so far?

It depends on how you measure it, right? How much money is generated? How many people’s lives you’ve saved? Or do you measure in terms of satisfaction? At Amazon, I helped invent something called the relational database service (RDS). It’s kind of a major component of the cloud-based services—AWS, Amazon Web Services (which provides on-demand cloud computing platforms and application programming interfaces on a metered pay-as-you-go basis). That was one of the things I had intuition about where it was going, and that was one of the reasons why I joined them. In this RDS, we generate about $10 billion dollars in revenue every year at this point. It’s one of the things I’m proud of. But until they retire the Hubble, I can still say that I’m particularly proud that every single thing that I’ve invented, or worked on over the course of my entire career is still being used today. Every single thing. That’s amazing.

What advice would you give students who want a similar career in the tech industry?

Walk into this assuming that you’re headed for a life of constant learning. I didn’t know that when I was starting. I’ve had a long career in a field that has very typically been thought of as a young person’s field. The hype is that it’s all the kids’ kind of thing, right? But you can become stagnated. You become bored—I never did this, but I could see someone being bored. If you think, “I’m going to learn this trade or I’m gonna learn how to work on websites . . . and that’s it,” one day, you will wake up and find out that the world has changed and you missed it. In the high tech industry, everything changes at an ever-increasing rate. You have to be constantly thirsting for the next thing, the next problem to solve, other opportunities or better ways to do things. If you’re not constantly learning, then you will become obsolete. I believe that a hundred percent. I’ve seen that happen a million times.

What’s your fondest Chico State memory?

That’s where I met my wife [Phyllis Kobrin (Information and Communication Studies, ’82)]. We were friends for a while before we actually got together. I met her about the time I was graduating (with a bachelor’s) and ended up staying to get my master’s, and “friends” became more. I didn’t know it was going to happen; that thing kind of sneaks up on you. And, well, here we are 37 years later. We both have fond memories of Chico, and we kind of reinforce them with each other.