Paradise Continues to Rebuild and Evolve Three Years After the Camp Fire

A rock decor inscribed “Home Sweet Home” is placed at a destroyed home from the Camp Fire along Newman Avenue, on Tuesday, March 12, 2019 in Paradise, Calif. The 153,336 acres Camp Fire was the deadliest and most destructive wildfire in California history started on November 8, 2018, in Butte County. (Jason Halley/University Photographer/CSU Chico)

By Jacquelyn Chase, Professor, Department of Geography and Planning; Peter Hansen, GIS Specialist, Department of Geography and Planning

Editor’s Note: A year after the Camp Fire, researchers Jacquelyn Chase and Peter Hansen explored how the population displaced by the blaze had relocated, literally, around the country. Now, they have new and updated data that look at updated new home construction permit numbers, what types of homes are being rebuilt (including what is actually affordable), and who has applied for grants to build or rebuild and where.

On November 8, 2018, Butte County experienced the most destructive fire in California history. Eighty-five people lost their lives in a conflagration that ultimately erased most of the Town of Paradise and unincorporated areas such as Concow, Butte Creek Canyon, and Magalia. In Paradise, over 10,000 homes were lost, representing 87 percent of the town’s housing. Most tree cover was also destroyed that day, as shown in the following time-lapse comparing aerial images from 2018 against 2021.

The removal of hazardous trees, burned vehicles, and toppled power poles, and cleanup of contaminated water systems and septic tanks went on for months. The population of Chico grew by 20 percent while thousands of other fire survivors moved to other cities and states. FEMA shelters stayed open until this September, and a host of social workers and community groups still serves those who are struggling with displacement and loss.

As the community approaches the three-year anniversary of Camp Fire, it has much to be proud of. Nonprofit organizations, businesses, and local officials have remained strongly committed to the recovery. There is recognition that recovery is an uneven process, and that some former residents need ongoing assistance. For example, the Paradise Town Council, with support from many in the community, has recently extended the urgency ordinance that has allowed almost 300 people to live in temporary housing on their properties while they rebuild.

After a disaster, community members and local officials often prioritize a quick rebuild and hope for the return of displaced people. This consensus is what led New Orleans to ultimately reject proposals to depopulate hazardous areas of the city after Hurricane Katrina. Similarly in Butte County and in Paradise, proposals to limit growth in the fire footprint have not been seriously entertained. Indeed, the town, county, and community have focused on rebuilding quickly. Rehousing displaced homeowners was given a Tier 1 priority in the Town of Paradise’s Recovery Plan.

The first two permits for single-family homes were processed in March 2019. By October 2021, the Town of Paradise had processed almost 2,000 permits for single-family residential units. In addition, over 100 permits for multifamily projects have been approved, representing 370 units.

The first two homes in Paradise were completed in July 2019. Of the total number of permits for single-family housing, 1,071 housing units have been finished as of September 2021—about half of the permits issued. The number of completions peaked in January 2021 at 82 homes and since then the monthly numbers have ranged between 44 and 62 completions. If an average of 50 homes are completed a month, the town could recover the balance of its destroyed housing stock (about 10,000 homes) in less than 20 years.

Rebuild or Recovery?

The replacement of housing is just one measure of recovery after a disaster. Net gains of housing or population in a recovery zone need to be disentangled to understand what those gains mean.

A full picture of recovery includes variables such as equity, community, vulnerability, displacement, and sustainability. The churn of ownership, property speculation, and the array of housing types being rebuilt can reveal if the recovery is inclusive. Two interrelated aspects of the housing rebuild in Paradise are (1) the degree to which affordable housing will be available, and (2) whether the rebuild is actually bringing back individuals who were displaced by the disaster.

We used data from four sources to map and describe these aspects of the recovery in Paradise, which represents 81 percent of housing rebuilds from the Camp Fire. The sources of information include data on permits and rebuilds from the Town of Paradise; real estate data on land and housing; County Assessor’s Office parcel data; and address change information available from direct mailing firms. The interactive map below shows single-family home building permits and home and lot sales as well as pre-fire structures, destroyed structures, and undamaged structures. Imagery from 2018 (pre-fire and immediate post fire) and from 2020 is also available. Toggle the layer list button to explore data layers—a full-screen view of this map is also available.

What is Being Rebuilt?

Mobile homes and motor homes were an important part of the affordable housing stock in Paradise before the Camp Fire, representing about one-fifth of all housing in the town in 2018. The fire destroyed 96 percent of these homes. Half of the mobile homes or motor homes were in mobile home parks. Almost all of the 32 mobile home parks once in Paradise remain unbuilt.

Difficulties with Pacific Gas & Electric installations have been just one of the complications with getting the parks up and running again. Land sales, home sales, and building permits for single-family homes fan out in all directions, as shown on the interactive map, but distinctly skirt around the ruins of the parks that were once home to many retirees of modest income.

Encouragingly, however, almost half of the permits are for potentially more affordable housing. Permits for manufactured housing, including mobile homes and modular homes, totaled over 600 of the total single-family homes, or about one-third, of all single-family home permits through September 2021.

There are over 100 permits for multi-housing projects representing 372 units, a little over half of which have been completed. Paradise Community Village is the largest multi-family project, with over 30 units. It was completed in September 2021 by the Community Housing Improvement Program (CHIP) and is dedicated to serving low-income families.

Half of the manufactured homes were two-bedroom units, and about 40 percent were three-bedroom units. The remaining 10 percent were split evenly between one-bedroom and four-bedroom units. Among “stick-built” single-family homes built on site, 32 percent were two-bedroom units and 54 percent were three-bedroom units. The remaining 14 percent were four-bedroom units or larger.

Altogether, one-bedroom homes totaled only 3.6 percent of permits, a sharp decline from the 12 percent of all housing units recorded by the census in 2010.

To put the problem of affordability in perspective, however, even a one-bedroom stick-built home may be out of reach to many survivors. This kind of home now costs about $300,000 to build.

Modular homes, a sub-category of manufactured homes, were promoted to survivors as an affordable option, but their cost has almost doubled since the fire. The most inexpensive two-bedroom modular home on offer by Pacific Modern Homes was $39,000 in September 2018 and $62,000 in June 2021, for example. According to the company, the kit price is only 25–35 percent of the final cost. Moving into that two-bedroom modular could cost almost $250,000. One advantage often touted for manufactured homes is the shorter period it takes to build them. All homes that were built within 1-2 months of permitting were manufactured homes of some kind, but one-quarter of the rebuilds that took over 12 months were of manufactured homes.

Who is Rebuilding?

Home builders are a mix of former residents, developers, and new residents. Those who rebuilt early were overwhelmingly people who had lost homes in the fire. Non-individual owners began showing up in the list of permits more than a year after the fire.

Rising housing costs, lack of insurance, and uncertainty around the PG&E settlement have kept many people from rebuilding on their properties. At the same time, the Town of Paradise began signaling that it welcomed residents and business owners from other areas. In December 2020, for example, town officials have expressed hope that Paradise could be a destination for urban people looking for more acreage.

The pace of building may differ between developers and homeowners. Of the 148 permits acquired by developers through September 2021, 43 homes, or 30 percent of these permits, had been completed. In contrast, 70 percent of homes permitted for individual owners have been completed.

Some individuals have taken out more than one building permit. They could be building rental homes or additional homes for family members, but they could also be building homes primarily as an investment strategy. In total, 37 individuals pulled multiple permits, totaling 152. Together with developers, they held 16 percent of the permits for single-family homes.

In addition, 44 percent of the permits issued for Paradise were for people who were not the original owners of the parcels. This includes a small number of people who had lived in Paradise before and were building at new addresses.

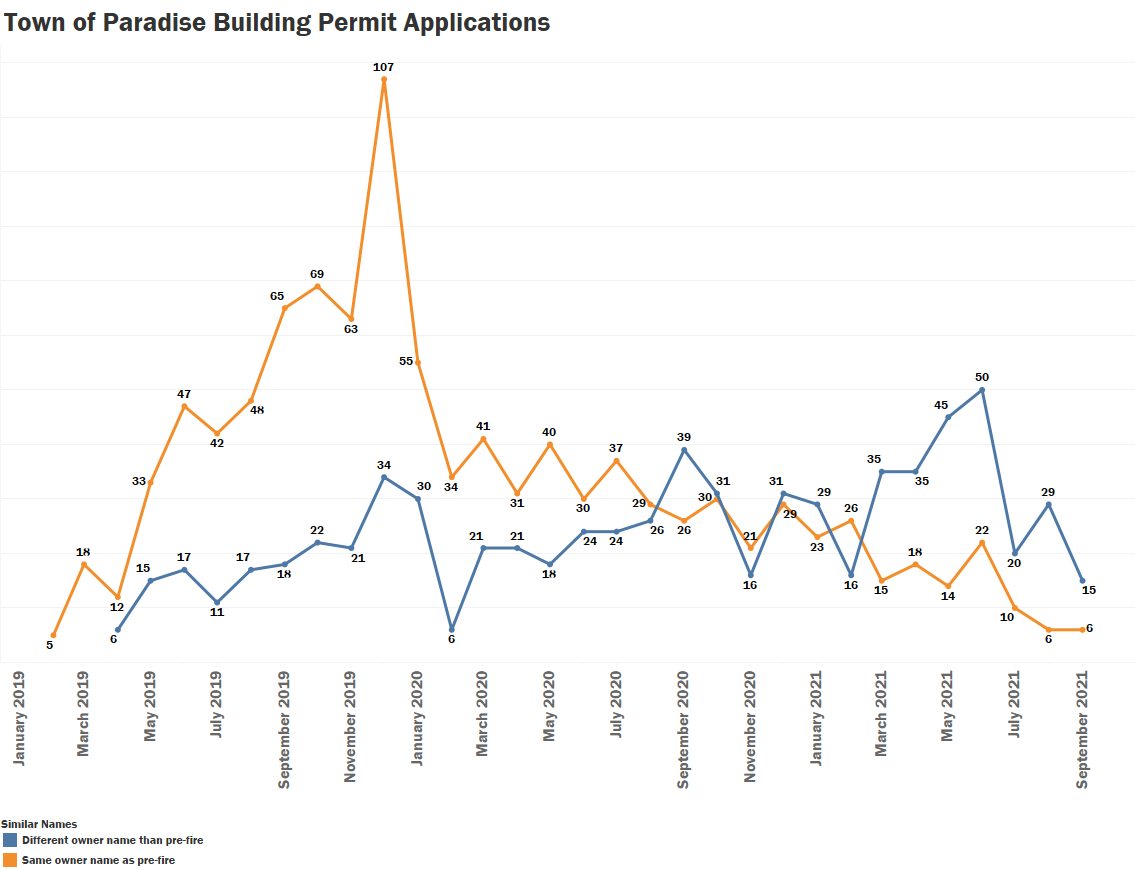

New owners now represent the majority of permit applicants, as shown in the following graphic.

The large proportion of new arrivals in Paradise is perhaps the clearest sign of a major dislocation. For myriad reasons, thousands of fire survivors will likely not return to Paradise. Meanwhile, over a third of Camp Fire survivors have changed address at least twice since the fire.

Where is Paradise?

Before November 2018, Paradise was home to 26,000 people who lived in a broad assortment of housing types in neighborhoods served by schools, a major hospital, churches, shopping centers, and even a large theater. Visualizations such as Google Street View show just how the Camp Fire made neighborhoods unrecognizable. Homes are separated by empty land, and the lush shield of tall pines and landscaping is gone, as shown in the animation here.

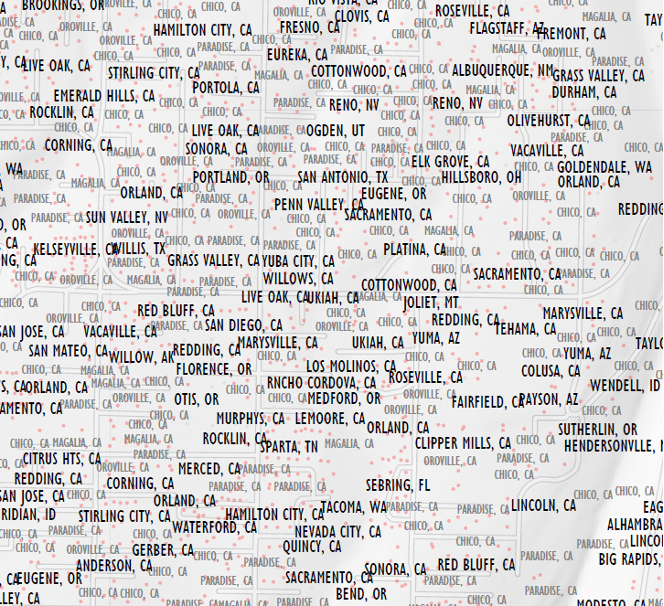

Perhaps most importantly, as residents look around them, old neighbors will be gone. Paradise is being rebuilt and the vegetation will grow back, but a new community, perhaps less affordable and less diverse, is already emerging. The following map section shows the places where former Paradise residents had moved to in the first year after the fire. The dark letters denote places outside of Butte County. For an interactive version of the map below, go here.

Additionally, Chase and Hansen have continued to track survivor changes of address. An estimated 1,200 addresses have been added to their map updated through September 2021, which shows the 14,250 last-known locations by city below. A full-screen view of this map is also available.

Jacquelyn Chase is a professor in the Department of Geography and Planning.

Peter Hansen (Geography, ’06; MA, Geography, ’12) is an IT consultant and GIS specialist within the Department of Geography and Planning and the College of Behavioral and Social Sciences.